In this post I will also introduce two concepts that are frequently used in software development world - DRY and “Convention over Configuration”. This post is a precursor to the upcoming FlexVPN configuration post on Packetpushers.

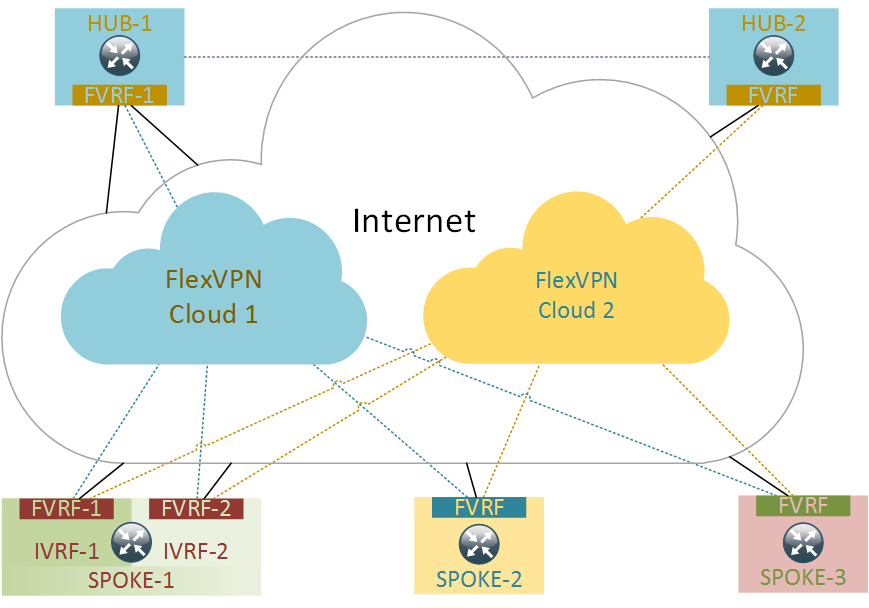

FlexVPN network overview

FlexVPN topology will consist of two FlexVPN “clouds”. Each cloud has a Hub router and multiple Spokes. Each Spoke is connected to each of the two Hubs thereby participating in both FlexVPN clouds. The two Hubs are interconnected by a direct site-to-site FlexVPN tunnel. To provide additional redundancy one Hub (HUB-1) and one Spoke (SPOKE-1) will have dual WAN links.

Assumptions

All FlexVPN devices will be using PKI-based authentication. However, in this post I will not cover the setup of PKI infrastructure and simply assume that all Hubs and Spokes are already enrolled with the appropriate CA. Following are the assumptions about the specifics of PKI setup on each router:

- Each FlexVPN cloud is defined by a unique domain name (e.g. cloud.one for HUB-1)

- Each Spoke has one X.509 certificate per FlexVPN cloud

- Spokes encode their WAN bandwidth in X.509 Organizational Unit (OU) attribute (e.g. RED corresponds to 50Mpbs)

- Each certificate’s trustpoint will be called “PKI-CLOUD-X”, where X is 1 or 2 depending on FlexVPN cloud

As an example, SPOKE-3 will have the following trustpoint configured for FlexVPN cloud #1:

crypto pki trustpoint PKI-CLOUD-1

enrollment url http://120.0.0.2:80

serial-number

fingerprint 2BE13A4FF167CEB770A24B2D6716033E

subject-name CN=SPOKE-3.cloud.one,OU=GREEN

vrf FVRF

revocation-check crl

rsakeypair CLOUD-1

auto-enroll

Convention over Configuration

This is where it’d make sense to introduce the concept of Convention over Configuration. The fact that we’ve assumed that all trustpoints will have the prefix of “PKI-CLOUD-” (convention) makes configuration templates a lot easier. Without it we could have allowed ANY naming of PKI trustpoint but then it should have been defined as a separate variable for every Spoke. Effectively we’re sacrificing some level flexibility in favour of brevity (and simplicity). This principle has been popularised by Ruby on Rails web framework and is widely used in other modern web frameworks.

FlexVPN inventory file

Before we start working with Ansible, we need to populate host inventory file. A parent “FLEXVPN” group will include two children groups - “HUBS” and “SPOKES”. The latter will be subdivided into three groups - “GREEN”, “BLUE” or “RED”. Each spoke will be assigned to a group base on its X.509 OU value. Additionally, in order to keep configuration templates simpler, we’ll treat multi-vrf SPOKE-1 as two different routers - SPOKE1_1 and SPOKE1_2:

[FLEXVPN:children]

HUBS

SPOKES

[HUBS]

HUB-1

HUB-2

[SPOKES:children]

GREEN

BLUE

RED

[RED]

SPOKE-1_1

SPOKE-1_2

[BLUE]

SPOKE-2

[GREEN]

SPOKE-3

Front-door VRF configuration

Another assumption is that all routers will have their Front-door VRF configured. Normally this would imply configuring an IP address on Internet-facing interface and a vrf-specific default route. In case of HUB-1, where there are two physical links in a single VRF, it is assumed that appropriate SLA-tied static routes are configured to enable dynamic failover between the two links. Here’s the example of how it’s done on HUB-1:

interface Ethernet0/0

vrf forwarding FVRF-1

ip address 120.0.0.2 255.0.0.0

!

interface Ethernet0/1

vrf forwarding FVRF-1

ip address 121.0.0.2 255.0.0.0

!

ip route vrf FVRF-1 0.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 120.0.0.1 track 1

ip route vrf FVRF-1 0.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 121.0.0.1 250

Environment variables and the DRY principle

One of the most obvious things to turn into a variable is the FVRF name and interface. We’ll put it into an Ansible’s global variable file ./group_vars/all. The same file will have a default BGP AS number for iBGP routing and a table mapping different OU values to their corresponding bandwidth in Kbps.

---

bgp_asn: 1

fvrf:

name: FVRF

interface: Ethernet0/0

bandwidth:

RED: 50000

GREEN: 20000

BLUE: 10000

Each of these variables can be overridden by a more specific host variable located in ./host_vars/ directory like it is the case with SPOKE1. All host-specific variables, like domain names, FlexVPN subnets, public addresses for Hub devices are also being stored in the same directory. Here’s an example of how HUB-1 overrides the default FVRF name and defines a few variables of its own:

---

primary: true

domain_name: cloud.one

nbma_ip: dynamic

dynamic:

- 120.0.0.2

- 121.0.0.2

vpn_ip: 169.254.1.1

subnet: 169.254.1.0/24

fvrf:

name: FVRF-1

Here it makes sense to talk about the DRY principle. All Spokes in their configuration files will use information like Hub’s NBMA address and domain name. So, in theory, we could have created a host variable file for each Spoke and stored that information there. However, in that case we would have multiple duplicate variables all storing the same value. This, obviously, creates a lot of problems when it comes to updating those variables. Instead of updating a value in a single place we now have to go and update every single Spoke’s host variables file. That’s why it’s important to NOT have ANY duplicates of ANY information in ANY part of your code, even if it comes at a price of an increased code complexity. This is widely accepted as best practice and used in almost every programming language and CS discipline.

FlexVPN configuration templates

I will omit the actual configuration templates for the sake of brevity. Those who are interested can check out my FlexVPN Github repository. Here’s how you can generate a full-blown config for FlexVPN network:

1 - Clone the Github repository

$ git clone https://github.com/networkop/flexvpn.git

2 - Update variables to match the network design

./hosts

./group_vars/all

./host_vars/

3 - Generate configuration files

$ ansible-playbook site.yml

All generated configuration files will be stored in ./files/ directory.

Conclusion

Thanks to DRY and Convention over Configuration principles it’s possible to devise a configuration template that will be the same for all Spokes. The actual configuration will consist of multiple components like IKEv2, dynamic VTI, AAA and BGP configuration. I’ll try to explain how they all tie together in my upcoming post on Packetpushers.