eBPF has a thriving ecosystem with a plethora of educational resources both on the subject of eBPF itself and its various application, including XDP. Where it becomes confusing is when it comes to the choice of libraries and tools to interact with and orchestrate eBPF. Here you have to select between a Python-based BCC framework, C-based libbpf and a range of Go-based libraries from Dropbox, Cilium, Aqua and Calico. Another important area that is often overlooked is the “productionisation” of the eBPF code, i.e. going from manually instrumented examples towards production-grade applications like Cilium. In this post, I’ll document some of my findings in this space, specifically in the context of writing a network (XDP) application with a userspace controller written in Go.

Choosing an eBPF library

In most cases, an eBPF library is there to help you achieve two things:

- Load eBPF programs and maps into the kernel and perform relocations, associating an eBPF program with the correct map via its file descriptor.

- Interact with eBPF maps, allowing all the standard CRUD operations on the key/value pairs stored in those maps.

Some libraries may also help you attach your eBPF program to a specific hook, although for networking use case this may easily be done with any existing netlink API library.

When it comes to the choice of an eBPF library, I’m not the only one confused (see [1],[2]). The truth is each library has its own unique scope and limitations:

- Calico implements a Go wrapper around CLI commands made with bpftool and iproute2.

- Aqua implements a Go wrapper around libbpf C library.

- Dropbox supports a small set of programs but has a very clean and convenient user API.

- IO Visor’s gobpf is a collection of go bindings for the BCC framework which has a stronger focus on tracing and profiling.

- Cilium and Cloudflare are maintaining a pure Go library (referred to below as

libbpf-go) that abstracts all eBPF syscalls behind a native Go interface.

For my network-specific use case, I’ve ended up using libbpf-go due to the fact that it’s used by Cilium and Cloudflare and has an active community, although I really liked (the simplicity of) the one from Dropbox and could’ve used it as well.

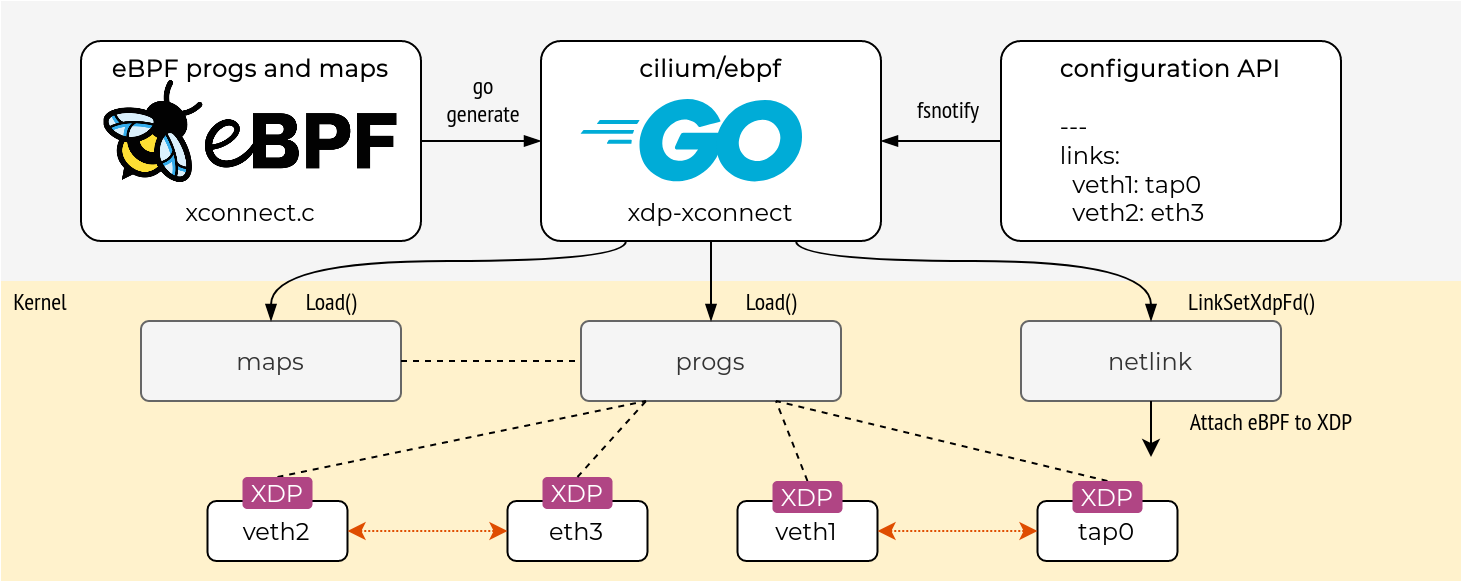

In order to familiarise myself with the development process, I’ve decided to implement an XDP cross-connect application, which has a very niche but important use case in network topology emulation. The goal is to have an application that watches a configuration file and ensures that local interfaces are interconnected according to the YAML spec from that file. Here is a high-level overview of how xdp-xconnect works:

The following sections will describe the application build and delivery process step-by-step, focusing more on integration and less on the actual code. Full code for xdp-xconnect is available on Github.

Step 1 - Writing the eBPF code

Normally this would be the main section of any “Getting Started with eBPF” article, however this time it’s not the focus. I don’t think I can help others learn how to write eBPF, however, I can refer to some very good resources that can:

- Generic eBPF theory is covered in a lot of details on ebpf.io and Cilium’s eBPF and XDP reference guide.

- The best place for some hands-on practice with eBPF and XDP is the xdp-tutorial. It’s an amazing resource that is definitely worth reading even if you don’t end up doing the assignments.

- Cilium source code and it’s analysis in [1] and [2].

My eBPF program is very simple, it consists of a single call to an eBPF helper function , which redirects all packets from one interface to another based on the index of the incoming interface.

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

SEC("xdp")

int xdp_xconnect(struct xdp_md *ctx)

{

return bpf_redirect_map(&xconnect_map, ctx->ingress_ifindex, 0);

}

In order to compile the above program, we need to provide search paths for all the included header files. The easiest way to do that is to make a copy of everything under linux/tools/lib/bpf/, however, this will include a lot of unnecessary files. So an alternative is to create a list of dependencies:

$ clang -MD -MF xconnect.d -target bpf -I ~/linux/tools/lib/bpf -c xconnect.c

Now we can make a local copy of only a small number of files specified in xconnect.d and use the following command to compile eBPF code for the local CPU architecture:

$ clang -target bpf -Wall -O2 -emit-llvm -g -Iinclude -c xconnect.c -o - | \

llc -march=bpf -mcpu=probe -filetype=obj -o xconnect.o

The resulting ELF file is what we’d need to provide to our Go library in the next step.

Step 2 - Writing the Go code

Compiled eBPF programs and maps can be loaded by libbpf-go with just a few instructions. By adding a struct with ebpf tags we can automate the relocation procedure so that our program knows where to find its map.

spec, err := ebpf.LoadCollectionSpec("ebpf/xconnect.o")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

var objs struct {

XCProg *ebpf.Program `ebpf:"xdp_xconnect"`

XCMap *ebpf.Map `ebpf:"xconnect_map"`

}

if err := spec.LoadAndAssign(&objs, nil); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer objs.XCProg.Close()

defer objs.XCMap.Close()

Type ebpf.Map has a set of methods that perform standard CRUD operations on the contents of the loaded map:

err = objs.XCMap.Put(uint32(0), uint32(10))

var v0 uint32

err = objs.XCMap.Lookup(uint32(0), &v0)

err = objs.XCMap.Delete(uint32(0))

The only step that’s not covered by libbpf-go is the attachment of programs to network hooks. This, however, can easily be accomplished by any existing netlink library, e.g. vishvananda/netlink, by associating a network link with a file descriptor of the loaded program:

link, err := netlink.LinkByName("eth0")

err = netlink.LinkSetXdpFdWithFlags(*link, c.objs.XCProg.FD(), 2)

Note that I’m using the SKB_MODE XDP flag to work around the exiting veth driver caveat. Although the native XDP mode is considerably faster than any other eBPF hook, SKB_MODE may not be as fast due to the fact that packet headers have to be pre-parsed by the network stack (see video).

Step 3 - Code Distribution

At this point everything should have been ready to package and ship our application if it wasn’t for one problem - eBPF code portability. Historically, this process involved copying of the eBPF source code to the target platform, pulling in the required kernel headers and compiling it for the specific kernel version. This problem is especially pronounced for tracing/monitoring/profiling use cases which may require access to pretty much any kernel data structure, so the only solution is to introduce another layer of indirection (see CO-RE).

Network use cases, on the other hand, rely on a relatively small and stable subset of kernel types, so they don’t suffer from the same kind of problems as their tracing and profiling counterparts. Based on what I’ve seen so far, the two most common code packaging approaches are:

- Ship eBPF code together with the required kernel headers, assuming they match the underlying kernel (see Cilium).

- Ship eBPF code and pull in the kernel headers on the target platform.

In both of these cases, the eBPF code is still compiled on that target platform which is an extra step that needs to be performed before the user-space application can start. However, there’s an alternative, which is to pre-compile the eBPF code and only ship the ELF files. This is exactly what can be done with bpf2go, which can embed the compiled code into a Go package. It relies on go generate to produce a new file with compiled eBPF and libbpf-go skeleton code, the only requirement being the //go:generate instruction. Once generated though, our eBPF program can be loaded with just a few lines (note the absence of any arguments):

specs, err := newXdpSpecs()

objs, err := specs.Load(nil)

The obvious benefit of this approach is that we no longer need to compile on the target machine and can ship both eBPF and userspace Go code in a single package or Go binary. This is great because it allows us to use our application not only as a binary but also import it into any 3rd party Go applications (see usage example).

Reading and Interesting References

Generic Theory:

https://github.com/xdp-project/xdp-tutorial

https://docs.cilium.io/en/stable/bpf/

https://qmonnet.github.io/whirl-offload/2016/09/01/dive-into-bpf/

BCC and libbpf:

https://facebookmicrosites.github.io/bpf/blog/2020/02/20/bcc-to-libbpf-howto-guide.html

https://nakryiko.com/posts/libbpf-bootstrap/

https://pingcap.com/blog/why-we-switched-from-bcc-to-libbpf-for-linux-bpf-performance-analysis

https://facebookmicrosites.github.io/bpf/blog/

eBPF/XDP performance:

https://www.netronome.com/blog/bpf-ebpf-xdp-and-bpfilter-what-are-these-things-and-what-do-they-mean-enterprise/

Linus Kernel Coding Style:

https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v5.9/process/coding-style.html

libbpf-go example programs:

https://github.com/takehaya/goxdp-template

https://github.com/hrntknr/nfNat

https://github.com/takehaya/Vinbero

https://github.com/tcfw/vpc

https://github.com/florianl/tc-skeleton

https://github.com/cloudflare/rakelimit

https://github.com/b3a-dev/ebpf-geoip-demo

bpf2go:

https://github.com/lmb/ship-bpf-with-go

https://pkg.go.dev/github.com/cilium/ebpf/cmd/bpf2go

XDP example programs:

https://github.com/cpmarvin/lnetd-ctl

https://gitlab.com/mwiget/crpd-l2tpv3-xdp