In the last post we’ve seen how to use Chef to automate the build of a 3-node OpenStack cloud. The only thing remaining is to build an underlay network supporting communication between the nodes, which is what we’re going to do next. The build process will, again, be relatively simple and will include only a few manual steps, but before we get there let me go over some of the decisions and assumptions I’ve made in my network design.

High-level design

The need to provide more bandwidth for East-West traffic has made the Clos Leaf-Spine architecture a de facto standard in any data centre network design. The use of virtual overlay networks has obviated the requirement to have a strict VLAN and IP numbering schemes in the underlay. The only requirement for the compute nodes now is to have any-to-any layer 3 connectivity. This is how the underlay network design has converged to a Layer 3 Leaf-Spine architecture.

The choice of a routing protocol is not so straight-forward. My fellow countryman Petr Lapukhov and co-authors of RFC draft claim that having a single routing protocol in your WAN and DC reduces complexity and makes interoperability and operations a lot easier. This draft presents some of the design principles that can be used to build a L3 data centre with BGP as the only routing protocol. In our lab we’re going to implement a single “cluster” of the multi-tier topology proposed in that RFC.

In order to help us build this in an automated and scalable way, we’re going to use a relatively new feature called unnumbered BGP.

Unnumbered BGP as a replacement for IGP

As we all know, one of the main advantages of interior gateway protocols is the automatic discovery of adjacent routers which is accomplished with the help of link-local multicasts. On the other hand, BGP traditionally required you to explicitly define neighbor’s IP address in order to establish a peering relationship with it. This is where IPv6 comes to the rescue. With the help of neighbor discovery protocol and router advertisement messages, it becomes possible to accurately determine the address of the peer BGP router on an intra-fabric link. The only question is how we would exchange IPv4 information over and IPv6-only BGP network.

RFC 5549, described an “extended nexthop encoding capability” which allows BGP to exchange routing updates with nexthops that don’t belong to the address family of the advertised prefix. In plain English it means that BGP is now capable of advertising an IPV4 prefix with an IPv6 nexthop. This makes it possible to configure all transit links inside the Clos fabric with IPv6 link-local addresses and still maintain reachability between the edge IPv4 host networks. Since nexthop IPs will get updated at every hop, there is no need for an underlying IGP to distribute them between all BGP routers. What we see is, effectively, BGP absorbing the functions of an IGP protocol inside the data centre.

Configuration example on Cumulus VX

In order to implement BGP unnumbered on Cumulus Linux all you need to is:

- Enable IPv6 router advertisements on all transit links

- Enable BGP on the same interfaces

Example Quagga configuration snippet will look like this:

interface swp1

ipv6 nd ra-interval 5

no ipv6 nd suppress-ra

rouer bgp <ASN>

neighbor swp1 interface

neighbor swp1 external

As you can see, Cumulus simplifies it even more by allowing you to only specify the BGP peering type (external/internal) and learning the value of peer BGP AS dynamically from a neighbor.

Design assumptions and caveats

With all the above in mind, this is the list of decisions I’ve made while building the fabric configuration:

- All switches inside the fabric will be running BGP peerings using IPv6 link-local addresses

- eBGP will be used throughout to simplify configuration automation (all peers will be external)

- Each Leaf/Spine switch will have a unique IPv4 loopback address assigned for management purposes (ICMP, SSH)

- On each Leaf switch all directly connected IPv4 prefixes will get redistributed into BGP

- BGP multipath rule will be “relaxed” to allow for different AS-PATHs. This is not used in our current topology but is required in an HA Leaf switch design (same IPv4 prefix will be advertised from two Leaf switches with different ASN)

- Loop prevention on Leaf switches will also be “relaxed”. This, again, is not used in our single “cluster” topology, however it will allow same Leaf ASNs to be reused in a different cluster.

Implementation steps

Picking up where we left off after the OpenStack node provisioning described in the previous post

Get the latest OpenStack lab cookbooks

git clone https://github.com/networkop/chef-unl-os.git cd chef-unl-osDownload and import Cumulus VX image similar to how it’s described here.

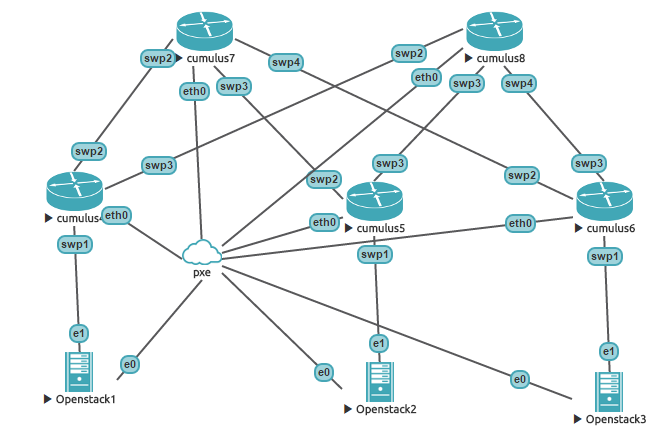

/opt/unetlab/addons/qemu/cumulus-vx/hda.qcow2Build the topology inside UNL. Make sure that Node IDs inside UNL match the ones in chef-unl-os/environment/lab.rb file and that interfaces are connected as shown in the diagram below

Re-run UNL self-provisioning cookbook to create a zero touch provisioning file and update DHCP server configuration with static entries for the switches.

chef-client -z -E lab -o pxeCumulus ZTP allows you to run a predefined script on the first boot of the operating system. In our case we inject a UNL VM’s public key and enable passwordless sudo for cumulus user.

Kickoff Chef provisioning to bootstrap and configure the DC fabric.

chef-client -z -E lab fabric.rbThis command instructs Chef provisioning to connect to each switch, download and install the Chef client and run a simple recipe to create quagga configuration file from a template.

At the end of step 5 we should have a fully functional BGP-only fabric and all 3 compute nodes should be able to reach each other in at most 4 hops.

[root@controller-1 ~]# traceroute 10.0.0.4

traceroute to 10.0.0.4 (10.0.0.4), 30 hops max, 60 byte packets

1 10.0.0.1 (10.0.0.1) 0.609 ms 0.589 ms 0.836 ms

2 10.255.255.7 (10.255.255.7) 0.875 ms 2.957 ms 3.083 ms

3 10.255.255.6 (10.255.255.6) 3.473 ms 5.486 ms 3.147 ms

4 10.0.0.4 (10.0.0.4) 4.231 ms 4.159 ms 4.115 ms