Table of Contents

Intro

This is going to be quite a lengthy blogpost so I’ll try to explain its structure first. I’ll start with a high level overview of components used to build virtual networks by examining 3 types of traffic:

- Unicast traffic between VM1 and VM2

- Unicast traffic between VM1 and the outside world (represented by an external subnet)

- Broadcast, Unknown unicast and Multicast or BUM traffic from VM1

Following that I’ll give a brief overview of how to interpret the configuration and dynamic state of OpenvSwitch to manually trace the path of a packet. This will be required for the next section where I’ll go over the same 3 types of traffic but this time corroborating every step with the actual outputs collected from the virtual switches. For the sake of brevity I’ll abridge a lot of the output to only contain the relevant information.

High Level Overview

Neutron server, residing in a control node, is responsible for orchestrating and provisioning of all virtual networks within an OpenStack environment. Its goal is to enable end-to-end reachability among the VMs and between the VMs and external subnets. To do that, Neutron uses concepts that should be very familiar to every network engineer like subnet, router, firewall, DHCP and NAT. In the previous post we’ve seen how to create a virtual router and attach it to public and private networks. We’ve also attached both of our VMs to a newly created private network and verified connectivity by logging into those virtual machines. Now let’s see how exactly these VMs communicate with each other and the outside world.

Unicast frame between VM1 and VM2

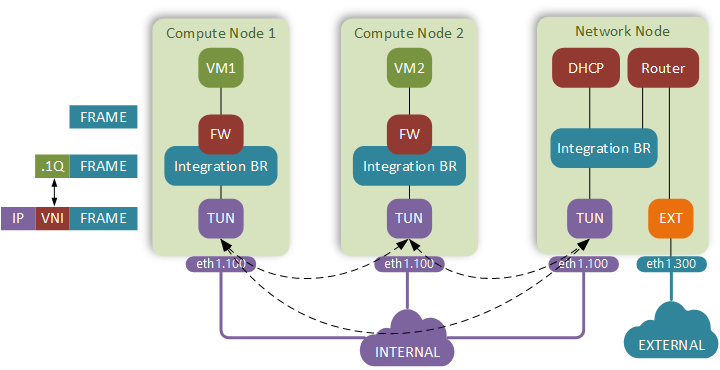

As soon as the frame leaves the vNIC of VM1 it hits the firewall. The firewall is implemented on a tap interface of the integration bridge. A set of ACL rules, defined in a Security Group that VM belongs to, gets translated into Linux iptables rules and attached to this tap interface. These simple reflexive access lists are what VMware and Cisco are calling microsegmentation and touting as one of the main use case of their SDN solutions.

Next our frame enters the integration bridge implemented using OpenvSwitch. Its primary function is to interconnect all virtual machines running on the host. Its secondary function is to provide isolation between different subnets and tenants by keeping them in different VLANs. VLAN IDs used for this are locally significant and don’t propagate outside of the physical host.

A dot1q-tagged packet is forwarded down a layer 2 trunk to the tunnel bridge, also implemented using OpenvSwitch. It is programmed to strip the dot1q tags, replace them with VXLAN headers and forward an IP/UDP packet with VXLAN payload on to the physical network.

Our simple routed underlay delivers the packets to the destination host, where the tunnel bridge swaps the VNI with a dot1q tag and forwards the packet up to the integration bridge.

Integration bridge consults the local MAC table, finds the output interface, clears the dot1q tag and send the frame up to the VM.

The frame gets screened by incoming iptables rules and gets delivered to the VM2.

Unicast frame between VM1 and External host

The first 3 steps will still be the same. VM1 sends a frame with destination MAC address of a virtual router. This packet will get encapsulated in a VXLAN header and forwarded to the Network node.

The tunnel and integration bridges of the network node deliver the packet to the private interface of a virtual router. This virtual router lives in a linux network namespaces (similar to VRFs) used to provide isolation between OpenStack tenants.

The router finds the outgoing interface (a port attached to the external bridge), and a next-hop IP which we have set when we configured a public subnet earlier.

The router then performs a source NAT on the packet before forwarding it out. This way the private IP of the VM stays completely hidden and hosts outside of OpenStack can talk back to the VM by sending packets to (publicly routable) external subnet.

External bridge (also an OpenvSwitch) receives the packet and forwards it out the attached physical interface (eth1.300).

BUM frame from VM1 for MAC address of VM2

VM1 sends a multicast frame, which gets examined by the iptables rules and enters the integration bridge.

The integration bridge follows the same process as for the unicast frame to assign the dot1q tag and floods the frame to the tunnel bridge.

The tunnel bridge sees the multicast bit in the destination MAC address and performs source replication by sending a duplicate copy of the frame to both compute host #2 and the network node.

Tunnel bridges of both receiving hosts strip the VXLAN header, add the dot1q tag and flood the frame to their respective integration bridges.

Integration bridges flood the frame within the VLAN identified by the dot1q header.

The response from VM2 follows the same process as the unicast frame.

One thing worth noting is when an ARP packet enters the integration bridge, its source IP address (in case of IPv4) or source MAC address (in case of IPv6) gets examined to make sure it belong to that VM. This is how ARP spoofing protection is implemented in OpenStack.

OpenvSwitch quick intro

Before we dive deeper into the details of the packet flows inside OVS let me give a brief overview of how it works. There are two main protocols to configure OVS:

OVSDB - a management protocol used to configure bridges, ports, VLANs, QoS, monitoring etc.

OpenFlow - used to install flow entries for traffic switching, similar to how you would configure a static route but allowing you to match on most of the L2-L4 protocol headers.

Control node instructs all local OVS agents about how to configure virtual networks. Each local OVS agent then uses these two protocols to configure OVS and install all the required forwarding entries. Each entry contains a set of matching fields (e.g. incoming port, MAC/IP addresses) and an action field which determines what to do with the packet. These forwarding entries are implemented as tables. This is how a packet traverses these tables:

First packet always hits table 0. The entries are examined in order of their priority (highest first) to find the first match. Note that it’s the first and not necessarily the more specific match. It’s the responsibility of a controller to build tables so that more specific flows are matched first. Normally this is done by assigning a higher priority to a more specific flow. Exact matches (where all L2-L4 fields are specified) implicitly have the highest priority value of 65535.

When a flow is matched, the action field of that flow is examined. Here are some of the most commonly used actions:

Action Description resubmit(X,) Resubmit a packet to table X output:Y Send a packet out port Y NORMAL Use a standard flood-and-learn behaviour of a switch to populate a local dynamic MAC address table learn(table=Z) Create an exact-match entry for the matched flow in table Z (we’ll see how its used later on) These actions can be combined in a sequence to create complex behaviours like sending the same packet to multiple ports for multicast source replication.

OVS also implements what Cisco calls Fast switching, where the first packet lookup triggers a cache entry to be installed in the kernel-space process to be used by all future packets from the same flow.

Detailed packet flow analysis

Let’s start by recapping what we know about our private virtual network. All these values can be obtained from Horizon GUI by examining the private network configuration under Project -> Network -> Networks -> private_network:

- VM1, IP=10.0.0.8, MAC=fa:16:3e:19:e4:91, port id = 258336bc-4f38-4bec-9229-4bc76e27f568

- VM2, IP=10.0.0.9, MAC=fa:16:3e:ab:1a:bf, port id = e5f7eaca-1a36-4b08-aa9b-14e9787f80b0

- Router, IP=10.0.0.1, MAC=fa:16:3e:cf:89:47, port id = 96dfc1d3-d23f-4d28-a461-fa2404767df2

The first 11 characters of port id will be used inside an integration bridge to build the port names, e.g.:

- tap258336bc-4f - interface connected to VM1

- qr-96dfc1d3-d2 - interface connected to the router

Enumerating OVS ports

In its forwarding entries OVS uses internal port numbers a lot, therefore it would make sense to collect all port number information before we start. This is how it can be done:

- Use

ovs-vsctl showcommand to collect information about existing port names and their attributes (e.g. dot1q tag, VXLAN tunnel IPs, etc). This is the output collected on compute host #1:

$ ovs-vsctl show | grep -E "Bridge|Port|tag|options"

Bridge br-tun

Port br-tun

Port patch-int

options: {peer=patch-tun}

Port "vxlan-0a00020a"

options: {df_default="true", in_key=flow, local_ip="10.0.1.10", out_key=flow, remote_ip="10.0.2.10"}

Port "vxlan-0a00030a"

options: {df_default="true", in_key=flow, local_ip="10.0.1.10", out_key=flow, remote_ip="10.0.3.10"}

Bridge br-int

Port br-int

Port "tap258336bc-4f"

tag: 5

Port patch-tun

options: {peer=patch-int}

- Use

ovs-ofctl dump-ports-desc <bridge_ID>command to correlate port names and numbers. Example below is for integration bridge of compute host #1:

$ ovs-ofctl dump-ports-desc br-int | grep addr

2(patch-tun): addr:5a:c5:44:fc:ac:72

7(tap258336bc-4f): addr:fe:16:3e:19:e4:91

LOCAL(br-int): addr:46:fe:10:de:1b:4f

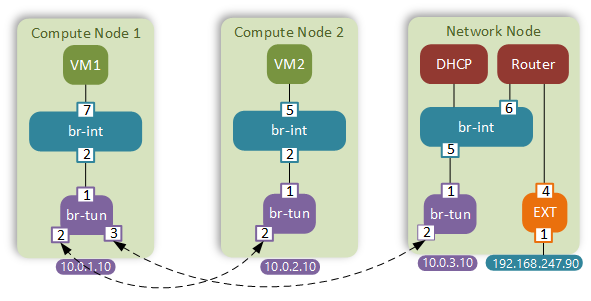

I’ve put together a diagram showing all the relevant integration bridge (br-int) and tunnel bridge (br-tun) ports on all 3 hosts.

Unicast frame between VM1 and VM2

1 - Frame enters the br-int on port 7. Default iptables rules allow all outbound traffic from a VM.

2 - Inside the br-int our frame is matched by the “catch-all” rule which triggers the flood-and-learn behaviour:

$ ovs-ofctl dump-flows br-int

table=0, priority=10,arp,in_port=7 actions=resubmit(,24)

table=0, priority=0 actions=NORMAL

3 - Since it’s a unicast frame the MAC address table is already populated by ARP:

$ ovs-appctl fdb/show br-int

port VLAN MAC Age

2 5 fa:16:3e:ab:1a:bf 1

Target IP address is behind port 2 which is where the frame gets forwarded next.

4 - Inside the tunnel bridge the frame will match three different tables. The first table simply matches the incoming port and resubmits the frame to table 2. Table 2 will match the unicast bit of the MAC address (the least significant bit of the first byte) and resubmit the frame to unicast table 20:

$ ovs-ofctl dump-flows br-tun

table=0, priority=1, in_port=1 actions=resubmit(,2)

table=2, priority=0, dl_dst=00:00:00:00:00:00/01:00:00:00:00:00 actions=resubmit(,20)

table=20, priority=1, vlan_tci=0x0005/0x0fff,dl_dst=fa:16:3e:ab:1a:bf actions=load:0->NXM_OF_VLAN_TCI[],load:0x54->NXM_NX_TUN_ID[],output:2

The final match is done on a VLAN tag and destination MAC address. Resulting action is a combination of three consecutive steps:

1 - Clear the dot1q tag - load:0->NXM_OF_VLAN_TCI[]

2 - Tag the frame with VNI 0x54 - load:0x54->NXM_NX_TUN_ID[]

3 - Send the frame to compute host 2 - output:2

This last match entry is quite interesting in a way that it contains the destination MAC address of VM2, which means this entry was created after the ARP process. In fact, as we’ll see in the next step, this entry is populated by a learn action triggered by the ARP response coming from VM2.

5 - A VXLAN packet arrives at compute host 2 and enters the tunnel bridge through port 2. It’s matched on the incoming port and resubmitted to a table where it is assigned with an internal VLAN ID 3 based on the matched tunnel id 0x54.

$ ovs-ofctl dump-flows br-tun

table=0, priority=1,in_port=2 actions=resubmit(,4)

table=4, priority=1,tun_id=0x54 actions=mod_vlan_vid:3,resubmit(,10)

table=10, priority=1 actions=learn(table=20,hard_timeout=300,priority=1,NXM_OF_VLAN_TCI[0..11],NXM_OF_ETH_DST[]=NXM_OF_ETH_SRC[],load:0->NXM_OF_VLAN_TCI[],load:NXM_NX_TUN_ID[]->NXM_NX_TUN_ID[],output:NXM_OF_IN_PORT[]),output:1

The last match does two things:

1 - Creates a mirroring entry in table 20 for the reverse packet flow. This is the entry similar to the one we've just seen in step 4. </li>

2 - Sends the packet towards the integration bridge.</li>

6 - The integration bridge checks the local dynamic MAC address table to find the MAC address of VM2(1a:bf).

$ ovs-appctl fdb/show br-int

port VLAN MAC Age

5 3 fa:16:3e:ab:1a:bf 0

7 - The frame is checked against the iptables rules configured on port 5 and gets sent up to VM2

Unicast frame to external host (192.168.247.1)

1 - The first 5 steps will be similar to the previous section. The only exception will be that the tunnel bridge of compute host 1 will send the VXLAN packet out port 3 towards the network node.

2 - The integration bridge of the network node consults the MAC address table to find the location of the virtual router (89:47) and forwards the packet out port 6.

$ ovs-appctl fdb/show br-int

port VLAN MAC Age

6 1 fa:16:3e:cf:89:47 1

3 - The virtual router does the route lookup to find the outgoing interface (qg-18bff97b-57)

$ ip route get 192.168.247.1

192.168.247.1 dev qg-18bff97b-57 src 192.168.247.90

Remember that since our virtual router resides in a network namespace all commands must be prepended with ip netns exec qrouter-uuid

4 - The virtual router performs the source IP translation to hide the private IP address:

$ iptables -t nat -S | grep qg-18bff97b-57

-A neutron-l3-agent-POSTROUTING ! -i qg-18bff97b-57 ! -o qg-18bff97b-57 -m conntrack ! --ctstate DNAT -j ACCEPT

-A neutron-l3-agent-snat -o qg-18bff97b-57 -j SNAT --to-source 192.168.247.90

By default all packets will get translated to the external address of the router. For each assigned floating IP address there will be a pair of source/destination NAT entries created in the same table.

5 - The router consults its local ARP table to find the MAC address of the next hop:

$ ip neigh show 192.168.247.1

192.168.247.1 dev qg-18bff97b-57 lladdr 00:50:56:c0:00:01 DELAY

6 - External bridge receives the frame from the virtual router on port 4, consults its own MAC address table built by ARP and forwards the packet to the final destination.

$ ovs-appctl fdb/show br-ex

port VLAN MAC Age

4 0 fa:16:3e:5c:90:e0 1

1 0 00:50:56:c0:00:01 1

BUM frame from VM1 for MAC address of VM2

1 - The integration bridge of the sending host will check the source IP of the ARP packet to make sure it hasn’t been spoofed before flooding the packet within the local broadcast domain (VLAN 5).

$ ovs-ofctl dump-flows br-int

table=0, priority=10,arp,in_port=7 actions=resubmit(,24)

table=24, priority=2,arp,in_port=7,arp_spa=10.0.0.8 actions=NORMAL

2 - The flooded packet reaches the tunnel bridge where it goes through 3 different tables. The first table matches the incoming interface, the second table matches the multicast bit of the MAC address.

$ ovs-ofctl dump-flows br-tun

table=0, priority=1,in_port=1 actions=resubmit(,2)

table=2, priority=0,dl_dst=01:00:00:00:00:00/01:00:00:00:00:00 actions=resubmit(,22)

table=22, dl_vlan=5 actions=strip_vlan,set_tunnel:0x54,output:3,output:2

The final table swaps the dot1q and VXLAN identifiers and does the source replication by forwarding the packet out ports 2 and 3. 3 - The following steps are similar to the unicast frame propagation with the exception that the local MAC table of the integration bridges will flood the packet to all interfaces in the same broadcast domain. That means that duplicate ARP requests will reach both the private interface of the virtual router and VM2. The latter, recognising its own IP, will send a unicast ARP response whose source IP will be verified by the ARP spoofing rule of the integration bridge. As the result of that process, both integration bridges on compute host 1 and 2 will populate their local MAC tables with addresses of VM1 and VM2.

Native OpenStack SDN advantages and limitation

Current implementation of OpenStack networking has several advantages compared to the traditional SDN solutions:

- Data-plane learning allows network to function even in the absence of the controller node

- Multicast source replication does not rely on multicast support in the underlay network

- ARP spoofing protection is the default security setting

However at this point it should also be clear that there a number of limitations that can impact the overall network scalability and performance:

- Multicast source replication creates unnecessary overhead by flooding ARP packets to all hosts

- All routed traffic has to go through the network node which becomes a bottleneck for the whole network

- There is no ability to control physical devices, even the ones that support OVSDB/Openflow

- Network node must be layer 2 adjacent with the external network segment

Things to explore next

In the following posts I’ll continue poking around Neutron and explore a number of features designed to address some of the limitations described above:

- L2 population

- Distributed Virtual Router

- L2 hardware gateway

- Network High Availability

- Load-Balancing-as-a-Service

- Open Virtual Network for OVS

- Neutron’s dynamic BGP routing

C2O

While writing this post I’ve compiled a list of commands most useful to query the state of OpenvSwitch. So now, inspired by a similar IOS to JUNOS (I2J) command conversion tables, I’ve put together my own Cisco to OVS conversion table, just for fun.

| Action | Cisco | OpenvSwitch |

|---|---|---|

| Show MAC address table | show mac address-table dynamic | ovs-appctl fdb/show <bridge_id> |

| Clear MAC address table | clear mac address-table dynamic | ovs-appctl fdb/flush <bridge_id> |

| Show port numbers | show interface status | ovs-ofctl dump-ports-desc <bridge_ID> |

| Show OVS configuration | show run | ovs-vsctl show |

| Show packet forwarding rules | show ip route | ovs-ofctl dump-flows <bridge_id> |

| Simulate packet flow | packet-tracer | ovs-appctl ofproto/trace <bridge_id> in_port=1 |

| View command history | show archive log config | ovsdb-tool show-log -m |

References

In this post I have glossed over some details like iptables and DHCP for the sake of brevity and readability. However this post wouldn’t be complete if I didn’t include references to other resources that contain a more complete, even if at times outdated, overview of OpenStack networking. This is also a way to pay tribute to blogs where I’ve learned most of what I was writing about here: