XML, just like many more structured data formats, was not designed to be human-friendly. That’s why many network engineers lose interest in YANG as soon as the conversation gets to the XML part. JSON is a much more human-readable alternative, however very few devices support RESTCONF, and the ones that do may have buggy implementations. At the same time, a lot of network engineers have happily embraced Ansible, which extensively uses YAML. That’s why I’ve decided to write a Python module that would program network devices using YANG and NETCONF according to configuration data described in a YAML format.

In the previous post I have introduced a new open-source tool called YDK, designed to create API bindings for YANG models and interact with network devices using NETCONF or RESTCONF protocols. I have also mentioned that I would still prefer to use pyangbind along with other open-source tools to achieve the same functionality. Now, two weeks later, I must admin I have been converted. Initially, I was planning to write a simple REST API client to interact with RESTCONF interface of IOS XE, create an API binding with pyangbind, use it to produce the JSON output, convert it to XML and send it to the device, similar to what I’ve described in my netconf and restconf posts. However, I’ve realised that YDK can already do all what I need with just a few function calls. All what I’ve got left to do is create a wrapper module to consume the YAML data and use it to automatically populate YDK bindings.

This post will be mostly about the internal structure of this wrapper module I call ydk_yaml.py, which will serve as a base library for a YANG Ansible module, which I will describe in my next post. This post will be very programming-oriented, I’ll start with a quick overview of some of the programming concepts being used by the module and then move on to the details of module implementation. Those who are not interested in technical details can jump straight to the examples sections at the end of this post for a quick demonstration of how it works.

Recursion

One of the main tasks of ydk_yaml.py module is to be able parse a YAML data structure. This data structure, when loaded into Python, is stored as a collection of Python objects like dictionaries, lists and primitive data types like strings, integers and booleans. One key property of YAML data structures is that they can be represented as trees and parsing trees is a very well-known programming problem.

After having completed this programming course I fell in love with functional programming and recursions. Every problem I see, I try to solve with a recursive function. Recursions are very interesting in a way that they are very difficult to understand but relatively easy to write. Any recursive function will consist of a number of if/then/else conditional statements. The first one (or few) if statements are called the base of a recursion - this is where recursion stops and the value is returned to the outer function. The remaining few if statements will implement the recursion by calling the same function with a reduced input. You can find a much better explanation of recursive functions here. For now, let’s consider the problem of parsing the following tree-like data structure:

{ 'parent': {

'child_1': {

'leaf_1': 'value_1'

},

'child_1': 'value_2'

}

}

Recursive function to parse this data structure written in a pseudo-language will look something like this:

def recursion(input_key, input_value):

if input_value is String:

return process(input_value)

elif input_value is Dictonary:

for key, value in input_value.keys_and_values():

return recursion(key, value)

The beauty of recursive functions is that they are capable parsing data structures of arbitrary complexity. That means if we had 1000 randomly nested child elements in the parent data structure, they all could have been parsed by the same 6-line function.

Introspection

Introspection refers to the ability of Python to examine objects at runtime. It can be useful when dealing with object of arbitrary structure, e.g. a YAML document. Introspection is used whenever there is a need for a function to behave differently based on the runtime data. In the above pseudo-language example, the two conditional statements are the examples of introspection. Whenever we need to determine the type of an object in Python we can either use a built-in function type(obj) which returns the type of an object or isinstance(obj, type) which checks if the object is an instance or a descendant of a particular type. This is how we can re-write the above two conditional statements using real Python:

if isinstance(input_value, str):

print('input value is a string')

elif isinstance(input_value, dict):

print('intput value is a dictionary')

Metaprogramming

Another programming concept used in my Python module is metaprogramming. Metaprogramming, in general, refers to an ability of programs to write themselves. This is what compilers normally do when they read the program written in a higher-level language and translate it to a lower-level language, like assembler. What I’ve used in my module is the simplest version of metaprogramming - dynamic getting and setting of object attributes. For example, this is how we would configure BGP using YDK Python binding, as described in my previous post:

bgp.id = 100

n = bgp.Neighbor()

n.id = '2.2.2.2'

n.remote_as = 65100

bgp.neighbor.append(n)

The same code could be re-written using the getattr and setattr method calls:

setattr(bgp, 'id', 100)

n = getattr(bgp, 'Neighbor')()

setattr(n, 'id', '2.2.2.2')

setattr(n, 'remote_as', 65100)

getattr(bgp, 'neighbor').append(n)

This is also very useful when working with arbitrary data structures and objects. In my case the goal was to write a module that would be completely independent of the structure of a particular YANG model, which means that I can not know the structure of the Python binding generated by YDK. However, I can “guess” the name of the attributes if I assume that my YAML document is structured exactly like the YANG model. This simple assumption allows me to implement YAML mapping for all possible YANG models with just a single function.

YANG mapping to YAML

As I’ve mentioned in my previous post, YANG is simply a way to define the structure of an XML document. At the same time, it is known that YANG-based XML can be mapped to JSON as described in this RFC. Since YAML is a superset of JSON, it’s easy to come up with a similar XML-to-YAML mapping convention. The following table contains the mapping between some of the most common YAML and YANG data structures and types:

| YANG data | YAML representation |

|---|---|

| container | dictionary |

| container name | dictionary key |

| leaf name | dictionary key |

| leaf | dictionary value |

| list | list |

| string, bool, integer | string, bool, integer |

| empty | null |

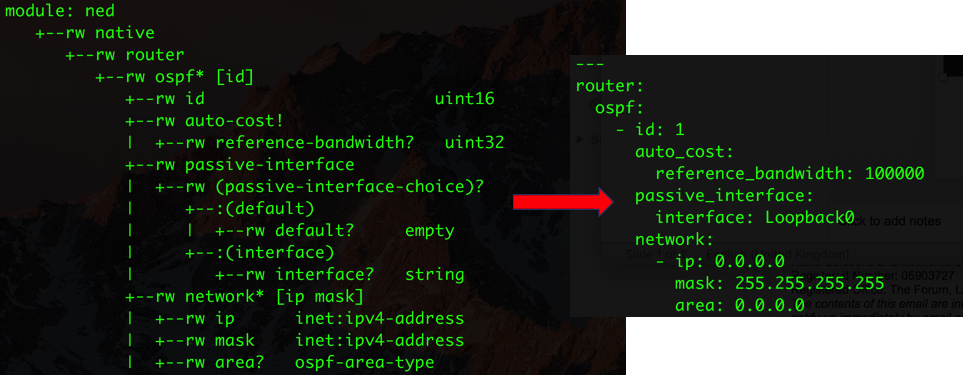

Using this table, it’s easy to map the YANG data model to a YAML document. Let me demonstrate it on IOS XE’s native OSPF data model. First, I’ve generated a tree representation of an OSPF data model using pyang:

pyang -f tree --tree-path "/native/router/ospf" ~/ydk-gen/gen-api/.cache/models/[email protected]/ned.yang -o ospf.tree

Next, I’ve trimmed it down to only contain the options that I would like to set and created a YAML document based on the model’s tree structure:

With the right knowledge of YANG model’s structure, it’s fairly easy to generate similar YAML configuration files for other configuration objects, like interface and BGP.

YANG instantiating function

At the heart of the ydk_yaml module is a single recursive function that traverses the input YAML data structure and uses it to instantiate the YDK-generated Python binding. Here is a simple, abridged version of the function that demonstrates the main logic.

def instantiate(binding, model_key, model_value):

if any(isinstance(model_value, x) for x in [str, bool, int]):

setattr(binding, model_key, model_value)

elif isinstance(model_value, list):

for el in model_value:

getattr(binding, model_key).append(instantiate(binding, model_key, el))

elif isinstance(model_value, dict):

container_instance = getattr(binding, model_key)()

for k, v in model_value.iteritems():

instantiate(container_instance, k, v)

setattr(binding, model_key, container_instance)

Most of it should already make sense based on what I’ve covered above. The first conditional statement is the base of the recursion and performs the action of setting the value of a YANG Leaf element. The second conditional statement takes care of a YANG List by traversing all its elements, instantiating them recursively, and appends the result to a YDK binding. The last elif statement creates a class instance for a YANG container, recursively populates its values and saves the final result inside a YDK binding.

The full version of this function covers a few extra corner cases and can be found here.

The YDK module wrapper

The final step is to write a wrapper class that would consume the YDK model binding along with the YAML data, and both instantiate and push the configuration down to the network device.

class YdkModel:

def __init__(self, model, data):

self.model = model

self.data = data

from ydk.models.cisco_ios_xe.ned import Native

self.binding = Native()

for k,v in self.data.iteritems():

instantiate(self.binding, k, v)

def action(self, crud_action, device):

from ydk.services import CRUDService

from ydk.providers import NetconfServiceProvider

provider = NetconfServiceProvider(address=device['hostname'],

port=device['port'],

username=device['username'],

password=device['password'],

protocol='ssh')

crud = CRUDService()

crud_instance = getattr(crud, crud_action)

crud_instance(provider, self.binding)

provider.close()

return

The structure of this class is pretty simple. The constructor instantiates a YDK native data model and calls the recursive instantiation function to populate the binding. The action method implements standard CRUD actions using the YDK’s NETCONF provider. The full version of this Python module can be found here.

Configuration examples

In my Github repo, I’ve included a few examples of how to configure Interface, OSPF and BGP settings of IOS XE device. A helper Python script 1_send_yaml.py accepts the YANG model name and the name of the YAML configuration file as the input. It then instantiates the YdkModel class and calls the create action to push the configuration to the device. Let’s assume that we have the following YAML configuration data saved in a bgp.yaml file:

+++

router:

bgp:

- id: 100

bgp:

router_id: 1.1.1.1

fast_external_fallover: null

update_delay: 15

neighbor:

- id: 2.2.2.2

remote_as: 200

- id: 3.3.3.3

remote_as: 300

redistribute:

connected: {}

To push this BGP configuration to the device all what I need to do is run the following command:

./1_send_yaml.py bgp bgp.yaml

The resulting configuration on IOS XE device would look like this:

router bgp 100

bgp router-id 1.1.1.1

bgp log-neighbor-changes

bgp update-delay 15

redistribute connected

neighbor 2.2.2.2 remote-as 200

neighbor 3.3.3.3 remote-as 300

To see more example, follow this link to my Github repo.