For quite a long time installation and deployment have been deemed as major barriers for OpenStack adoption. The classic “install everything manually” approach could only work in small production or lab environments and the ever increasing number of project under the “Big Tent” made service-by-service installation infeasible. This led to the rise of automated installers that over time evolved from a simple collection of scripts to container management systems.

Evolution of automated OpenStack installers

The first generation of automated installers were simple utilities that tied together a collection of Puppet/Chef/Ansible scripts. Some of these tools could do baremetal server provisioning through Cobbler or Ironic (Fuel, Compass) and some relied on server operating system to be pre-installed (Devstack, Packstack). In either case the packages were pulled from the Internet or local repository every time the installer ran.

The biggest problem with the above approach is the time it takes to re-deploy, upgrade or scale the existing environment. Even for relatively small environments it could be hours before all packages are downloaded, installed and configured. One of the ways to tackle this is to pre-build an operating system with all the necessary packages and only use Puppet/Chef/Ansible to change configuration files and turn services on and off. Redhat’s TripleO is one example of this approach. It uses a “golden image” with pre-installed OpenStack packages, which is dd-written bit-by-bit onto the baremetal server’s disk. The undercloud then decides which services to turn on based on the overcloud server’s role.

Another big problem with most of the existing deployment methods was that, despite their microservices architecture, all OpenStack services were deployed as static packages on top of a shared operating system. This made the ongoing operations, troubleshooting and ugprades really difficult. The obvious thing to do would be to have all OpenStack services (e.g. Neutron, Keyston, Nova) deployed as containers and managed by a container management system. The first company to implement that, as far as I know, was Canonical. The deployment process is quite complicated, however the end result is a highly flexible OpenStack cloud deployed using LXC containers, managed and orchestrated by Juju controller.

Today (September 2017) deploying OpenStack services as containers is becoming mainstream and in this post I’ll show how to use Kolla to build container images and Kolla-Ansible to deploy them on a pair of “baremetal” VMs.

Lab overview

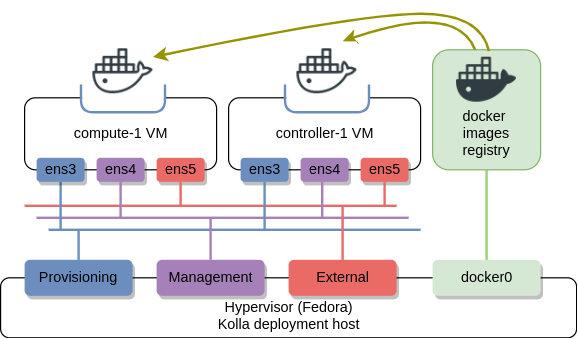

My lab consists of a single controller and a single compute VM. The goal was to make them as small as possible so they could run on a laptop with limited resources. Both VMs are connected to three VM bridged networks - provisioning, management and external VM access.

I’ve written some bash and Ansible scripts to automate the deployment of VMs on top of any Fedora derivative (e.g. Centos7). These scripts should be run directly from the hypervisor:

git clone https://github.com/networkop/kolla-odl-bgpvpn.git && cd kolla-odl-bgpvpn

./1-create.sh do

./2-bootstrap.sh do

The first bash script downloads the VM OS (Centos7), creates two blank VMs and sets up a local Docker registry. The second script installs all the dependencies, including Docker and Ansible.

Building OpenStack docker containers with Kolla

The first step in Kolla deployment workflow is deciding where to get the Docker images. Kolla maintains a Docker Hub registry with container images built for every major OpenStack release. The easiest way to get them would be to pull the images from Docker hub either directly or via a pull-through caching registry.

In my case I needed to build the latest version of OpenStack packages, not just the latest major release. I also wanted to build a few additional, non-OpenStack images (Opendaylight and Quagga). Because of that I had to build all Docker images locally and push them into a local docker registry. The procedure to build container images is very well documented in the official Kolla image building guide. I’ve modified it slightly to include the Quagga Dockerfile and automated it so that the whole process can be run with a single command:

./3-build.sh do

This step can take quite a long time (anything from 1 to 4 hours depending on the network and disk I/O speed), however, once it’s been done these container images can be used to deploy as many OpenStack instances as necessary.

Deploying OpenStack with Kolla-Ansible

The next step in OpenStack deployment workflow is to deploy Docker images on target hosts. Kolla-Ansible is a highly customizable OpenStack deployment tool that is also extemely easy to use, at least for people familiar with Ansible. There are two main sources of information for Kolla-Ansible:

- Global configuration file (/etc/kolla/globals.yaml), which contains some of the most common customization options

- Ansible inventory file (/usr/share/kolla-ansible/ansible/inventory/*), which maps OpenStack packages to target deployment hosts

To get started with Kolla-Ansible all what it takes is a few modifications to the global configuration file to make sure that network settings match the underlying OS interface configuration and an update to the inventory file to point it to the correct deployment hosts. In my case I’m making additional changes to enable SFC, Skydive and Tacker and adding files for Quagga container, all of which can be done with the following command:

./4-deploy.sh do

The best thing about this method of deployment is that it takes (in my case) under 5 minutes to get the full OpenStack cloud from scratch. That means if I break something or want to redeploy with some major changes (add/remove Opendaylight), all what I have to do is destroy the existing deployment (approx. 1 minute), modify global configuration file and re-deploy OpenStack. This makes Kolla-Ansible an ideal choice for my lab environment.

Overview of containerized OpenStack

Once the deployment has been completed, we should be able to see a number of running Docker containers - one for each OpenStack process.

root@compute-1# docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

0bb8a8eeb1a9 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-skydive-agent:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days skydive_agent

63b5b643dfae 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-neutron-openvswitch-agent:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days neutron_openvswitch_agent

f6f74c5982cb 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-openvswitch-vswitchd:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days openvswitch_vswitchd

3078421a3892 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-openvswitch-db-server:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days openvswitch_db

9146c16d561b 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-nova-compute:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days nova_compute

8079f840627f 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-nova-libvirt:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days nova_libvirt

220d617d31a5 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-nova-ssh:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days nova_ssh

743ce602d485 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-cron:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days cron

8b71f08d2781 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-kolla-toolbox:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days kolla_toolbox

f76d0a7fcf2a 172.26.0.1:5000/kolla/centos-source-fluentd:5.0.0 "kolla_start" 3 days ago Up 3 days fluentd

All the standard docker tools are available to interact with those containers. For example, this is how we can see what processes are running inside a container:

root@compute-1# docker exec nova_compute ps -www aux

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

nova 1 0.0 0.0 188 4 pts/3 Ss+ Sep04 0:00 /usr/local/bin/dumb-init /bin/bash /usr/local/bin/kolla_start

nova 7 0.7 1.3 2292560 134896 ? Ssl Sep04 35:33 /var/lib/kolla/venv/bin/python /var/lib/kolla/venv/bin/nova-compute

root 86 0.0 0.3 179816 32900 ? S Sep05 0:00 /var/lib/kolla/venv/bin/python /var/lib/kolla/venv/bin/privsep-helper --config-file /etc/nova/nova.conf --privsep_context vif_plug_ovs.privsep.vif_plug --privsep_sock_path /tmp/tmpFvP0GS/privsep.sock

Some of you may have noticed that none of the containers expose any ports. So how do they communicate? The answer is very simple - all containers run in a host networking mode, effectively disabling any network isolation and giving all contaners access to TCP/IP stacks of their Docker hosts. This is a simple way to avoid having to deal with Docker networking complexities, while at the same time preserving the immutability and portability of Docker containers.

All containers are configured to restart in case of a failure, however there’s no CMS to provide full lifecycle management and advanced scheduling. If upgrade of scale-in/out is needed, Kolla-Ansible will have to be re-run with updated configuration options. There is sibling project called Kolla-Kubernetes (still under developement), that’s designed to address some of the mentioned shortcomings.

Coming up

Now that the lab is up we can start exploring the new OpenStack SDN features. In the next post I’ll have a close look at Neutron’s SFC feature, how to configure it and how it’s been implemented in OVS forwarding pipeline.