REST SDK Design

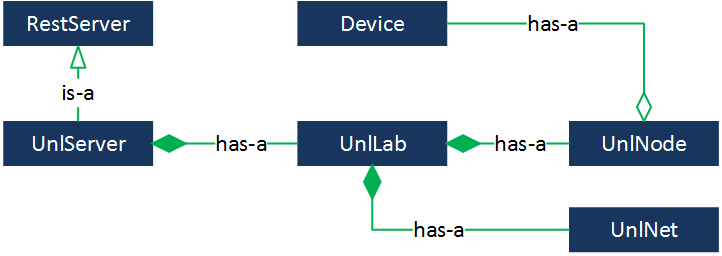

As it is with networks, design is a very crucial part of programming. I won’t pretend to be an expert in that field and merely present the way I’ve built REST SDK. Fortunately, a lot of design will mimic the objects and their relationship on the server side. I’ll slightly enhance it to improve code re-use and portability. Here are the basic objects:

- RestServer - implements basic application-agnostic HTTP CRUD logic

- UnlServer - an extension of a RestServer with specific authentication method (cookie-based) and several additional methods

- Device - an instance of a network device with specific attributes like type, image name, number of CPUs

- UnlLab - a lab instance existing inside a UnlServer

- UnlNode - a node instance existing inside a UnlLab

- UnlNet - a network instance also existing inside a UnlLab object

All these objects and their relationships are depicted on the following simplified UML diagram. If you’re interested in what different connections mean you can read this guide.

Here I’ve used inheritance to extend RestServer functionality to make a UnlServer. This makes sense because UnlServer object will re-use a lot of the methods from the RestServer. I could have combined them in a single object but I’ve decided to split the application-agnostic bit into a separate component to allow it to be re-used by other RESTful clients in the future.

The other objects are aggregated and interact through code composition, where Lab holds a pointer to the UnlServer where it was created, Nodes and Nets point to the Lab in which they live. Composition creates loose coupling between objects, while still allowing method delegation and code re-use.

For additional information about Composition vs Inheritance you can go here, here or here.

REST SDK Implementation

Throughout this post I’ll be omitting a lot of the non-important code. For full working code refer to the link at the end of this post.

RestServer implementation

When RestServer object is created, __init__() function takes the server IP address and constructs a base_url, a common prefix for all API calls. The 4 CRUD actions are encoded into names of the methods implementing them, for example to send an Update one would need to call .update_object(). This convention will make the implementation of UnlServer a lot more readable. Each of the 4 CRUD methods call _send_request() with correct HTTP verb preset (the leading underscore means that this method is private and should only be called from within the RestServer class).

class RestServer(object):

def __init__(self, address):

self.cookies = None

self.base_url = '/'.join(['http:/', address, 'api'])

def _send_request(self, method, path, data=None):

response = None

url = self.base_url + path

try:

response = requests.request(method, url, json=data, cookies=self.cookies)

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print('*** Error calling %s: %s', url, e.message)

return response

def get_object(self, api_call, data=None):

return self._send_request('GET', api_call, data)

def add_object(self, api_call, data=None):

return self._send_request('POST', api_call, data)

def update_object(self, api_call, data=None):

return self._send_request('PUT', api_call, data)

def del_object(self, api_call, data=None):

return self._send_request('DELETE', api_call, data)

def set_cookies(self, cookie):

self.cookies = cookie

At this stage RestServer does very simple exception and no HTTP response error handling. I’ll show how to extend it to do authentication error handling in the future posts.

UnlServer implementation

At the very top of the unetlab.py file we have a REST_SCHEMA global variable providing mapping between actions and their respective API calls. This improves code readability (at least to me) and makes future upgrades to API easier to implement.

UnlServer class is extending the functionality of a RestServer by implementing UNetLab-specific methods. For example, login() sends username and password using the add_object() method of the parent class and sets the cookies extracted from the response to allow all subsequent methods to be authenticated.

REST_SCHEMA = {

'login': '/auth/login',

'logout': '/auth/logout',

'status': '/status',

'list_templates': '/list/templates/'

}

class UnlServer(RestServer):

def __init__(self, address):

super(UnlServer, self).__init__(address)

def login(self, user, pwd):

api_call = REST_SCHEMA['login']

payload = {

"username": user,

"password": pwd

}

resp = self.add_object(api_call, data=payload)

self.set_cookies(resp.cookies)

return resp

def logout(self):

api_call = REST_SCHEMA['logout']

resp = self.get_object(api_call)

return resp

def get_status(self):

api_call = REST_SCHEMA['status']

resp = self.get_object(api_call)

return resp

def get_templates(self):

api_call = REST_SCHEMA['list_templates']

resp = self.get_object(api_call)

return resp

As you can see all methods follow the same pattern:

- Extract an API url from

REST_SCHEMAglobal variable - Send a request using one of the 4 CRUD methods of the parent RestServer class

- Return the response

Now let’s see how we can use TDD approach to build out the rest of the code.

Test-driven development

The easiest way to test RESTful application is by observing the status code of the returned HTTP response. If it is 200 or 201 then it can be considered successful. The biggest challenge is to make sure each test case is independent from one another. One option is to include all the code required by a test case inside the function that implements it. This, however, may lead to long and unwieldy spaghetti-code and breaks the DRY principle.

To help avoid that, TDD frameworks often have fixtures - functions that are run before and after every test case, designed to setup and cleanup the test environment. In our case we can use fixtures to login before each test case is run and logoff after it’s finished. Let’s see how we can use Python’s built-in unittest framework to drive the REST SDK development process.

First let’s define our base class UnlTests who’s sole purpose will be to implement authentication fixtures. All the test cases will go into child classes that can either reuse and extend these fixtures. This is how test cases for the already existing code look like:

class UnlTests(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

self.unl = UnlServer(UNETLAB_ADDRESS)

resp = self.unl.login(USERNAME, PASSWORD)

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

def tearDown(self):

resp = self.unl.logout()

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

class BasicUnlTests(UnlTests):

def test_status(self):

resp = self.unl.get_status()

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

def test_templates(self):

resp = self.unl.get_templates()

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

At this point if you add all the necessary import statements and populate global variables with correct IP addresses and credentials all tests should pass. Now let’s add another test case to retrieve user information from UNL:

class BasicUnlTests(UnlTests):

...

def test_user_info(self):

resp = self.unl.get_user_info()

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

Rerun the tests and watch the last one fail saying 'UnlServer' object has no attribute 'get_user_info'. Now let’s go back to our UNL SDK code and add that attribute:

REST_SCHEMA = {

... ,

'get_user_info': '/auth'

}

class UnetLab(RestServer):

...

def get_user_info(self):

api_call = REST_SCHEMA['get_user_info']

resp = self.get_object(api_call)

return resp

Rerun the test_unl.py now and watch all tests succeed again. The same iterative approach can be used to add any number of new methods at the same time making sure none of the existing functionality is affected.

Note that these are very simple tests and they only verify the response code and not its contents. The better approach would be to look inside the payload and verify, for example, that username is admin.

UnlLab and UnlNode implementation

Now let’s revert back to normal coding style for a second and create classes for Labs and Nodes. As per the design, these should be separate objects but they should contain a pointer to the context in which they exist. Therefore, it makes sense to instantiate a Lab inside a UnlServer, a Node inside a Lab and pass in the self (UnlServer or Lab) as an argument. For example, here is how a lab will be created:

REST_SCHEMA = {

... ,

'create_lab': '/labs'

}

class UnlServer(RestServer):

...

def create_lab(self, name):

return UnlLab(self, name)

class UnlLab(object):

def __init__(self, unl, name):

api_call = REST_SCHEMA['create_lab']

payload = {

"path": "/",

"name": name,

"version": "1"

}

self.name = name

self.unl = unl

self.resp = self.unl.add_object(api_call, data=payload)

So to create a Lab we need to issue a .create_lab() call on UnlServer object and give it a labname. That function will return a new Lab object with the following attributes preset:

- Lab name -

self.name - UnlServer that created it -

self.unl - HTTP response returned by the server after the Create CRUD action -

self.resp

The latter can be used to check if the creation was successful (and potentially throw an error if it wasn’t). The structure of the payload can be found in API docs.

Nodes will be created in a similar way with a little exception. Apart from the name, Node also needs to know about the particulars of the device it will represent (like device type, image name etc.). That’s where Device class comes in. The implementation details are very easy and can be found on Github so I won’t provide them here. The only function of a Device at this stage is to create a dictionary that can be used as a payload in create_node API request.

REST_SCHEMA = {

... ,

'create_node': '/labs/{lab_name}/nodes',

}

class UnlLab(object):

...

def create_node(self, device):

return UnlNode(self, device)

class UnlNode(object):

def __init__(self, lab, device):

self.unl = lab.unl

self.lab = lab

self.device = device

api_call = REST_SCHEMA['create_node']

api_url = api_call.format(api_call, lab_name=append_unl(self.lab.name))

payload = self.device.to_json()

self.resp = self.unl.add_object(api_url, data=payload)

Take a quick look at how the api_url is created. We’re using .format() method (built-into string module) to substitute a named variable {format} with the actual name of the lab (self.lab.name). That labname gets appended with an extension by a helper function append_unl. That helper function, along with the others we’ll define in the future, can also be found on Github.

Back to TDD

Let’s use TDD again to add the last two actions we’ll cover in this post.

- Get list of all Nodes

- Delete a lab

class BasicUnlLabTest(UnlTests):

def test_create_lab(self):

self.unl.delete_lab(LAB_NAME)

resp = self.unl.create_lab(LAB_NAME).resp

self.unl.delete_lab(LAB_NAME)

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

def test_delete_lab(self):

self.unl.create_lab(LAB_NAME)

resp = self.unl.delete_lab(LAB_NAME)

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

def test_get_nodes(self):

lab = self.unl.create_lab(LAB_NAME)

resp = lab.get_nodes()

self.unl.delete_lab(LAB_NAME)

self.assertEqual(200, resp.status_code)

As a challenge, try implementing the SDK logic for the last two failing methods yourself using UNL API as a reference. You can always refer the the link at the end of the post if you run into any problems.

Simple App

So far we’ve created and deleted objects with REST API but haven’t seen the actual result. Let’s start writing an app that we’ll continue to expand in the next post. In this post we’ll simply login and create a lab containing a single node.

from restunl.unetlab import UnlServer

from restunl.device import Router

LAB_NAME = 'test_1'

def app_1():

unl = UnlServer('192.168.247.20')

unl.login('admin', 'unl')

print ("*** CONNECTED TO UNL")

lab = unl.create_lab(LAB_NAME)

print ("*** CREATED LAB")

node_1 = lab.create_node(Router('R1'))

print ("*** CREATED NODE")

if __name__ == '__main__':

app_1()

Run this once, then login the UNL web GUI and navigate to test_1 lab. Examine how node R1 is configured and compare it to the defaults set in a Device module.

Source code

All code from this post can be found in my public repository on Github