The idea of using Ansible for configuration changes and state verification is not new. However the approach I’m going to demonstrate in this post, using YANG and NETCONF, will have a few notable differences:

- I will not use any templates and absolutely no XML/JSON for device config generation

- All changes will be pushed through a single, vendor and model-independent Ansible module

- State verification will be done with no pattern-matching or screen-scraping

- All configuration and operational state will be based on a couple of YAML files

- To demonstrate the model-agnostic behaviour I will use a mixture of vendor’s native, IETF and OpenConfig YANG models

I hope this promise is exciting enough so without further ado, let’s get cracking.

Environment setup

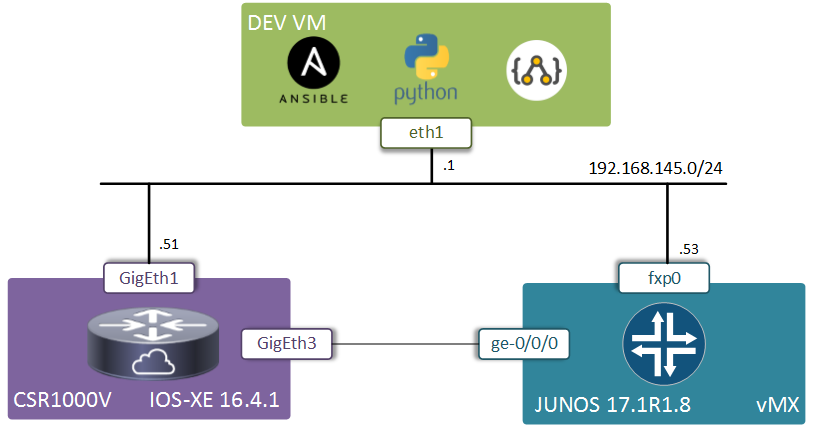

The test environment will consist of a single instance of CSR1000v running IOS-XE version 16.4.1 and a single instance of vMX running JUNOS version 17.1R1.8. The VMs containing the two devices are deployed within a single hypervisor and connected with one interface to the management network and back-to-back with the second pair of interfaces for BGP peering.

Each device contains some basic initial configuration to allow it be reachable from the Ansible server.

interface GigabitEthernet1

ip address 192.168.145.51 255.255.255.0

!

netconf-yang

netconf-yang cisco-odm polling enable

netconf-yang cisco-odm actions parse Interfaces

vMX configuration is quite similar. Static MAC address is required in order for ge interfaces to work.

set system login user admin class super password admin123

set system services netconf

set interface fxp0 unit 0 family inet address 192.168.145.53/24

set interface ge-0/0/0 mac 00:0c:29:fc:1a:b7

Ansible playbook configuration

My Ansible-101 repository contains two plays - one for configuration and one for state verification. The local inventory file contains details about the two devices along with the login credentials. All the work will be performed by a custom Ansible module stored in the ./library directory. This module is a wrapper for a ydk_yaml module described in my previous post. I had to heavily modify the original ydk_yaml module to work around some Ansible limitations, like the lack of support for set data structures.

This custom Ansible module also relies on a number of YDK Python bindings to be pre-installed. Refer to my YAML, Operational and JUNOS repositories for the instructions on how to install those modules.

The desired configuration and expected operational state are documented inside a couple of device-specific host variable files. For each device there is a configuration file config.yaml, describing the desired configuration state. For IOS-XE there is an additional file verify.yaml, describing the expected operational state using the IETF interface YANG model (I couldn’t find how to get the IETF or OpenConfig state models to work on Juniper).

All of these files follow the same structure:

- Root container can be either

configorverifyand defines how the enclosed data is supposed to be used - First nested container has to match the top-most container of a YANG model. For example it could be bgp-state for cisco-bgp-state.yang or openconfig-bgp for openconfig-bgp.yang model

- The remaining nested data has to follow the structure of the original YANG model as described in my previous post.

Here’s how IOS-XE will be configured, using IETF interfaca YANG models (to unshut the interface) and Cisco’s native YANG model for interface IP and BGP settings:

---

config:

interfaces:

interface:

- name: GigabitEthernet3

enabled: true

native:

interface:

gigabitethernet:

- name: '3'

description: P2P link

ip:

address:

primary:

address: 12.12.12.1

mask: 255.255.255.0

loopback:

- name: 0

description: ROUTER ID

ip:

address:

primary:

address: 1.1.1.1

mask: 255.255.255.255

router:

bgp:

- id: 65111

bgp:

router_id: 1.1.1.1

neighbor:

- id: 12.12.12.2

remote_as: 65222

redistribute:

connected:

empty: empty

For JUNOS configuration, instead of the default humongous native model, I’ll use a set of much more light-weight OpenConfig YANG models to configure interfaces, BGP and redistribution policies:

---

config:

openconfig-interfaces:

interface:

- name: ge-0/0/0

subinterfaces:

subinterface:

- index: 0

ipv4:

addresses:

address:

- ip: 12.12.12.2/24

config:

ip: 12.12.2.2

prefix_length: 24

- name: lo0

subinterfaces:

subinterface:

- index: 0

ipv4:

addresses:

address:

- ip: 2.2.2.2/32

config:

ip: 2.2.2.2

prefix_length: 32

openconfig-policy:

policy_definitions:

policy_definition:

- name: CONNECTED->BGP

statements:

statement:

- name: Loopback0

conditions:

match_interface:

config:

interface: lo0

subinterface: 0

actions:

config:

accept_route: empty

openconfig-bgp:

global_:

config:

as_: 65222

neighbors:

neighbor:

- neighbor_address: 12.12.12.1

config:

peer_group: YANG

peer_as: 65111

peer_groups:

peer_group:

- peer_group_name: YANG

config:

peer_as: 65111

apply_policy:

config:

export_policy:

- CONNECTED->BGP

Configuration

Both devices now can be configured with just a single command:

ansible-playbook config.yaml

Behind the scenes, Ansible calls my custom ydk_module and passes to it the full configuration state and device credentials. This module then constructs an empty YDK binding based on the name of a YANG model and populates it recursively with the data from the config container. Finally, it pushes the data to the device with the help of YDK NETCONF service provider.

Verification

There’s one side to YANG which I have carefully avoided until now and it’s operational state models. These YANG models are built similarly to configuration models, but with a different goal - to extract the running state from a device. The reason why I’ve avoided them is that, unlike the configuration models, the current support for state models is limited and somewhat brittle.

For example, JUNOS natively only supports state models as RPCs, where each RPC represents a certain show command which, I assume, when passed to the devices gets evaluated, its output parsed and result returned back to the client. With IOX-XE things are a little better with a few of the operational models available in the current 16.4 release. You can check out my Github repo for some examples of how to check the interface and BGP neighbor state between the two IOS-XE devices. However, most of the models are still missing (I’m not counting the MIB-mapped YANG models) in the current release. The next few releases, though, are promised to come with an improved state model support, including some OpenConfig models, which is going to be super cool.

So in this post, since I couldn’t get JUNOS OpenConfig models report any state and my IOS-XE BGP state model wouldn’t return any output unless the BGP peering was with another Cisco device or in the Idle state, I’m going to have to resort to simply checking the state of physical interfaces. This is how a sample operational state file would look like (question marks are YAML’s special notation for sets which is how I decided to encode Enum data type):

---

verify:

interfaces-state:

interface:

- name: GigabitEthernet3

oper_status:

? up

- name: Loopback0

oper_status:

? up

- name: GigabitEthernet2

oper_status:

? down

Once again, all expected state can be verified with a single command:

ansible-playbook verify.yaml

If the state defined in that YAML file matches the data returned by the IOS-XE device, the playbook completes successfully. You can check that it works by shutting down one of the GigabitEthernet3 or Loopback0 interfaces and observing how Ansible module returns an error.

Outro

Now that I’ve come to the end of my YANG series of posts I feel like I need to provide some concise and critical summary of everything I’ve been through. However, if there’s one thing I’ve learned in the last couple of months about YANG, it’s that things are changing very rapidly. Both Cisco and Juniper are working hard introducing new models and improving support for the existing ones. So one thing to keep in mind, if you’re reading this post a few months after it was published (April 2017), is that some or most of the above limitations may not exist and it’s always worth checking what the latest software release has to offer.

Finally, I wanted to say that I’m a strong believer that YANG models are the way forward for network device configuration and state verification, despite the timid scepticism of the networking industry. I think that there are two things that may improve the industry’s perception of YANG and help increase its adoption:

Support from networking vendors - we’ve already seen Cisco changing by introducing YANG support on IOS-XE instead of producing another dubious One-PK clone. So big thanks to them and I hope that other vendors will follow suit.

Tools - this part, IMHO, is the most crucial. In order for people to start using YANG models we have to have the right tools that would be versatile enough to allow network engineers to be limited only by their imagination and at the same time be as robust as the CLI. So I wanted to give a big shout out to all the people contributing to open-source projects like pyang, YDK and many others that I have missed or don’t know about. You’re doing a great job guys, don’s stop.