Recently I’ve been pondering the idea of cloud-like method of consumption of traditional (physical) networks. My main premise for this was that users of a network don’t have to wait hours or days for their services to be provisioned when all that’s required is a simple change of an access port. Let me reinforce it by an example. In a typical data center network, the configuration of the core (fabric) is fairly static, while the config at the edge can change constantly as servers get added, moved or reconfigured. Things get even worse when using infrastructure-as-code with CI/CD pipelines to generate and test the configuration since it’s hard to expose only a subset of it all to the end users and it certainly wouldn’t make sense to trigger a pipeline every time a vlan is changed on an edge port.

This is where Network-as-a-Service (NaaS) platform fits in. The idea is that it would expose the required subset of configuration to the end user and will take care of applying it to the devices in a fast and safe way. In this series of blogposts I will describe and demonstrate a prototype of such a platform, implemented on top of Kubernetes, using Napalm as southbound API towards the devices.

Frameworkless automation

One thing I’ve decided NOT to do is build NaaS around a single automation framework. The tendency to use a single framework to solve all sorts of automation problems can lead to a lot of unnecessary hacking and additional complexity. When you’re finding yourself constantly writing custom libraries to perform some logic that can not be done natively within the framework, perhaps it’s time to step back and reassess your tools. The benefit of having a single tool, may not be worth the time and effort spent customising it. A much better approach is to split the functionality into multiple services and standardise what information is supposed to be passed between them. Exactly what microservices architecture is all about. You can still use frameworks within each service if it makes sense, but these can be easily swapped when a newer and better alternative comes along without causing a platform-wide impact.

One problem that needs to be solved, however, is where to run all these microservices. The choice of Kubernetes here may seem like a bit of a stretch to some since it can get quite complicated to troubleshoot and manage. However, in return, I get a number of constructs (e.g. authentication, deployments, ingress) that are an integral part of any platform “for free”. After all, as Kelsey Hightower said:

Kubernetes is a platform for building platforms. It's a better place to start; not the endgame.

— Kelsey Hightower (@kelseyhightower) November 27, 2017

So here is a list of reasons why I’ve decided to build NaaS on top of Kubernetes:

- I can define arbitrary APIs (via custom resources) with whatever structure I like.

- These resources are stored, versioned and can be exposed externally.

- With openAPI schema, I can define the structure and values of my APIs (similar to YANG but much easier to write).

- I get built-in multitenancy through namespaces.

- I get AAA with Role-based Access Control, and not just a simple passwords-in-a-text file kind of AAA, but proper TLS-based authentication with oAuth integration.

- I get a client-side code with libraries in python, js and go.

- I get admission controls that allow me to mutate (e.g. expand interface ranges) and validate (e.g. enforce per-tenant separation) requests before they get accepted.

- I get secret management to store sensitive information (e.g. device inventory)

- All data is stored in etcd, which can be easily backed up/restored.

- All variables, scripts, templates and data models are stored as k8s configmap resources and can be retrieved, updated and versioned.

- Operator pattern allows me to write a very simple code to “watch” the incoming requests and do some arbitrary logic described in any language or framework of my choice.

Not to mention all of the more standard capabilities like container orchestration, lifecycle management and auto-healing.

The foundation of NaaS

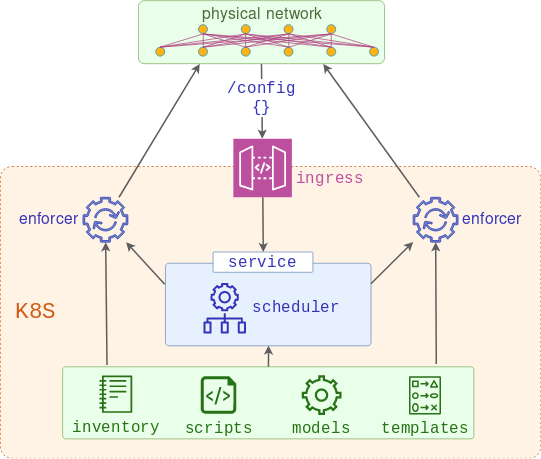

Before I get to the end-user API part, I need to make sure I have the mechanism to modify the configuration of my network devices. Below is the high-level diagram that depicts how this can be implemented using two services:

- Scheduler - a web server that accepts requests with the list of devices to be provisioned and schedules the enforcers to push it. This service is built on top of a K8s deployment which controls the expected number and health of scheduler pods and recreates them if any one of them fails.

- Enforcer - one or more job runners created by the scheduler, combining the data models and templates and using the result to replace the running configuration of the devices. This service is ephemeral as jobs will run to completion and stop, however, logs can still be viewed for some time after the completion.

Scheduler architecture

Scheduler, just like all the other services in NaaS, is written in Python. The web server component has a single webhook that handles incoming HTTP POST requests with JSON payload containing the list of devices.

@app.route("/configure", methods=["POST"])

def webhook():

log.info(f"Got incoming request from {request.remote_addr}")

payload = request.get_json(force=True)

devices = payload.get("devices")

The next thing it does is read the device inventory mounted as a local volume from the Kubernetes secret store and decide how many devices to schedule on a single runner. This gives the flexibility to change the number of devices processed by a single runner (scale-up vs scale-out).

sliced_inventory = [x for x in inv_slicer(devices_inventory, step)]

schedule(sliced_inventory)

Finally, for each slice of the inventory, scheduler creates a Kubernetes job based on a pre-defined template, with base64-encoded inventory slice as an environment variable.

t = Template(job_template)

job_manifest = t.render(

job={"name": job_name, "inventory": encode(inventory_slice)}

)

return api.create_namespaced_job(

get_current_namespace(), yaml.safe_load(job_manifest), pretty=True

)

In order for the scheduler to function, it needs to have several supporting Kubernetes resources:

- Deployment to perform the lifecycle management of the app

- Service to expose the deployed application internally

- Ingress to expose the above service to the outside world

- Configmap to store the actual python script

- Secret to store the device inventory

- RBAC rules to allow scheduler to read configmaps and create jobs

Most of these resources (with the exception of configmaps) are defined in a single manifest file.

Enforcer architecture

The current implementation of the enforcer uses Nornir together with Jinja and Napalm plugins. The choice of the framework here is arbitrary and Nornir can easily be replaced with Ansible or any other framework or script. The only coupling between the enforcer and the scheduler is the format of the inventory file, which can be changed quite easily if necessary.

The enforcer runner is built out of two containers. The first one to run is an init container that decodes the base64-encoded inventory and saves it into a file that is later used by the main container.

encoded_inv = os.getenv("INVENTORY", "")

decoded_inv = base64.b64decode(encoded_inv)

inv_yaml = yaml.safe_load(decoded_inv.decode())

The second container is the one that runs the device configuration logic. Firstly, it retrieves the list of all device data models and templates and passes them to the push_config task.

models = get_configmaps(labels={"app": "naas", "type": "model"})

templates = get_configmaps(labels={"app": "naas", "type": "template"})

result = nr.run(task=push_config, models=models, templates=templates)

Inside that task, a list of sorted data models get combined with jinja templates to build the full device configuration:

for ordered_model in sorted(my_models):

model = yaml.safe_load(ordered_model.data.get("structured-config"))

template_name = ordered_model.metadata.annotations.get("template")

for template in templates:

if template.metadata.name == template_name:

r = task.run(

name=f"Building {template_name}",

task=template_string,

template=template.data.get("template"),

model=model,

)

cli_config += r.result

cli_config += "\n"

Finally, we push the resulting config to all the devices in the local inventory:

result = task.run(

task=networking.napalm_configure,

replace=True,

configuration=task.host["config"],

)

Demo

Before we begin the demonstration, I wanted to mention a few notes about my code and test environments:

- All code for this blogpost series will be stored in NaaS Github repository, separated in different tagged branches (part-1, part-2, etc.)

- For this and subsequent demos I’ll be using a couple of Arista EOS devices connected back-to-back with 20 interfaces.

- All bash commands, their dependencies and variables are stored in a number of makefiles in the

.mkdirectory. I’ll provide the actual bash commands only when it’s needed for clarity, but all commands can be looked up in makefiles.

The code for this post can be downloaded here.

Build the test topology

Any two EOS devices can be used as a testbed, as long as they can be accessed over eAPI. I build my testbed with docker-topo and c(vEOS) image. This step will build a local topology with two containerised vEOS-lab devices:

make topo

Build the local Kubernetes cluster

The following step will build a docker-based kind cluster with a single control plane and a single worker node.

make kubernetes

Check that the cluster is functional

The following step will build a base docker image and push it to dockerhub. It is assumed that the user has done docker login and has his username saved in DOCKERHUB_USER environment variable.

export KUBECONFIG="$(kind get kubeconfig-path --name="naas")"

make warmup

kubectl get pod test

This is a 100MB image, so it may take a few minutes for test pod to transition from ContainerCreating to Running

Deploy the services

This next command will perform the following steps:

- Upload the enforcer and scheduler scripts as configmaps.

- Create Traefik (HTTP proxy) daemonset to be used as ingress.

- Upload generic device data model along with its template and label them accordingly.

- Create a deployment, service and ingress resources for the scheduler service.

make scheduler-build

If running as non-root, the user may be prompted for a sudo password.

Test

In order to demonstrate how it works, I will do two things. First, I’ll issue a POST request from my localhost to the address registered on ingress (http://api.naas/configure) with payload requesting the provisioning of all devices.

wget -O- --post-data='{"devices":["all"]}' --header='Content-Type:application/json' http://api.naas/configure

A few seconds later, we can view the logs of the scheduler to confirm that it received the request:

kubectl logs deploy/scheduler

2019-06-13 10:29:22 INFO scheduler - webhook: Got incoming request from 10.32.0.3

2019-06-13 10:29:22 INFO scheduler - webhook: Request JSON payload {'devices': ['all']}

2019-06-13 10:29:22 INFO scheduler - get_inventory: Reading the inventory file

2019-06-13 10:29:22 INFO scheduler - webhook: Scheduling 2 devices on a single runner

2019-06-13 10:29:22 INFO scheduler - create_job: Creating job job-eiw829

We can also view the logs of the scheduled Nornir runner:

kubectl logs jobs/job-eiw829

2019-06-13 10:29:27 INFO enforcer - push_configs: Found models: ['generic-cm']

2019-06-13 10:29:27 INFO enforcer - push_configs: Downloading Template configmaps

2019-06-13 10:29:27 INFO enforcer - get_configmaps: Retrieving the list of ConfigMaps matching labels {'app': 'naas', 'type': 'template'}

Finally, when logged into one of the devices, we should see the new configuration changes applied, including the new alias:

devicea#show run | include alias

alias FOO BAR

Another piece of configuration that has been added is a special event-handler that issues an API call to the scheduler every time its startup configuration is overwritten. This may potentially be used as an enforcement mechanism to prevent anyone from saving the changes done manually, but included here mainly to demonstrate the scheduler API:

devicea#show run | i alias

alias FOO BAR

devicea#conf t

devicea(config)#no alias FOO

devicea(config)#end

devicea#write

Copy completed successfully.

devicea#show run | i alias

devicea#show run | i alias

alias FOO BAR

Coming up

Now that we have the mechanism to push the network changes based on models and templates, we can start building the user-facing part of the NaaS platform. In the next post, I’ll demonstrate the architecture and implementation of a watcher - a service that listens to custom resources and builds a device interface data model to be used by the scheduler.