There comes a time in the life of every Kubernetes cluster when internal resources (pods, deployments) need to be exposed to the outside world. Doing so from a pure IP connectivity perspective is relatively easy as most of the constructs come baked-in (e.g. NodePort-type Services) or can be enabled with an off-the-shelf add-on (e.g. Ingress and LoadBalancer controllers). In this post, we’ll focus on one crucial piece of network connectivity which glues together the dynamically-allocated external IP with a static customer-defined hostname — a DNS. We’ll examine the pros and cons of various ways of implementing external DNS in Kubernetes and introduce a new CoreDNS plugin that can be used for dynamic discovery and resolution of multiple types of external Kubernetes resources.

External Kubernetes Resources

Let’s start by reviewing various types of “external” Kubernetes resources and the level of networking abstraction they provide starting from the lowest all the way to the highest level.

One of the most fundamental building block of all things external in Kubernetes is the NodePort service. It works by allocating a unique external port for every service instance and setting up kube-proxy to deliver incoming packets from that port to the one of the healthy backend pods. This service is rarely used on its own and was designed to be a building block for other higher-level resources.

Next level up is the LoadBalancer service which is one of the most common ways of exposing services externally. This service type requires an extra controller that will be responsible for IP address allocation and delivering traffic to the Kubernetes nodes. This function can be implemented by cloud load-balancers, in case the cluster is deployed one of the public clouds, a physical appliance or a cluster add-on like MetalLB or Porter.

At the highest level of abstraction is the Ingress resource. It, too, requires a dedicated controller which spins up and configures a number of proxy servers that can act as a L7 load-balancer, API gateway or, in some cases, a L4 (TCP/UDP) proxy. Similarly to the LoadBalancer, Ingress may be implemented by one of the public cloud L7 load-balancers or could be self-hosted by the cluster using any one of the open-source ingress controllers. Amongst other things, Ingress controllers can perform TLS offloading and named-based routing which rely heavily on external DNS infrastructure that can dynamically discover Ingress resources as they get added/removed from the cluster.

There are other external-ish resources like ExternalName services and even ClusterIP in certain cases. They represent a very small subset of corner case scenarios and are considered outside of the scope of this article. Instead, we’ll focus on the two most widely used external resources—LoadBalancers and Ingresses, and see how they can be integrated into the public DNS infrastructure.

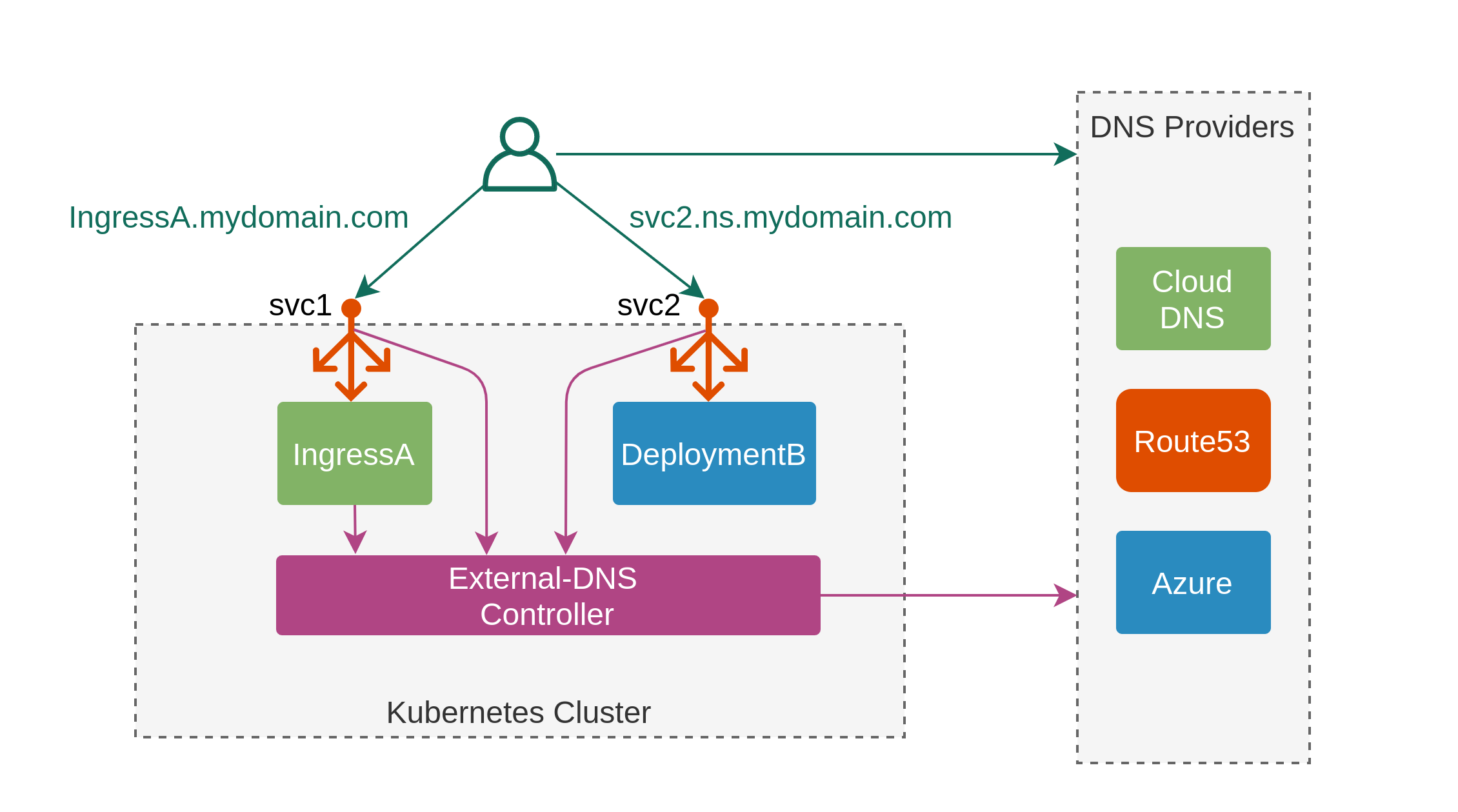

ExternalDNS

The most popular solution today is the ExternalDNS controller. It works by integrating with one of the public DNS providers and populates a pre-configured DNS zone with entries extracted from the monitored objects, e.g. Ingress’s spec.rules[*].host or Service’s external-dns.alpha.kubernetes.io/hostname annotations. In addition, it natively supports non-standard resources like Istio’s Gateway or Contour’s IngressRoute which, together with the support for over 15 cloud DNS providers, makes it a default choice for anyone approaching this problem for the first time.

ExternalDNS is an ideal solution for Kubernetes clusters under a single administrative domain, however, it does have a number of trade-offs that start to manifest themselves when a cluster is shared among multiple tenants:

- Multiple DNZ zones require a dedicated ExternalDNS instance per zone.

- Each new zone requires cloud-specific IAM rules to be set up to allow ExternalDNS to make the required changes.

- Unless managing a local cloud DNS, API credentials will need to be stored as a secret inside the cluster.

In addition to the above, ExternalDNS represents another layer of abstraction and complexity outside of the cluster that needs to be considered during maintenance and troubleshooting. Every time the controller fails, there’s a possibility of some stale state to be left, accumulating over time and polluting the hosted DNS zone.

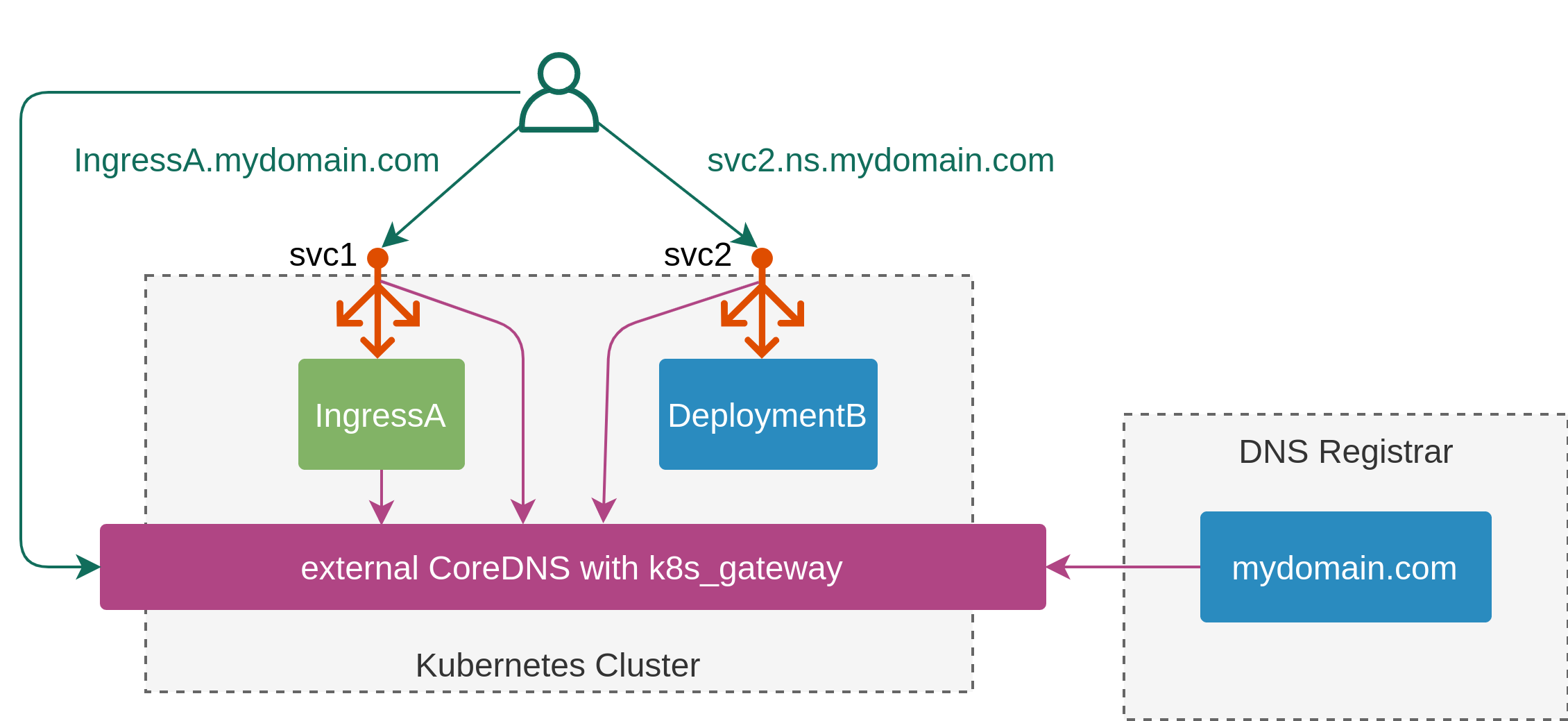

CoreDNS’s k8s_external plugin

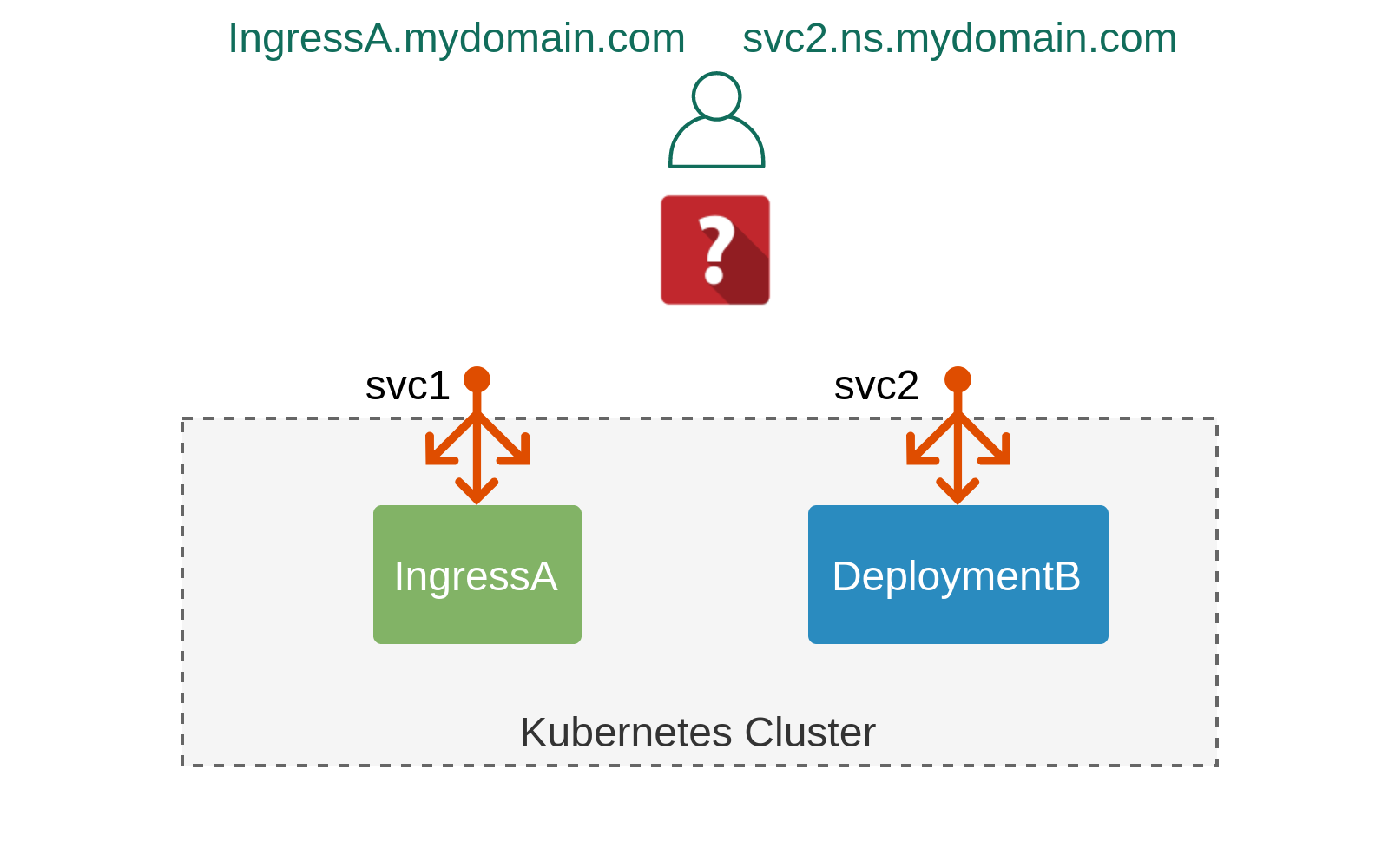

An alternative approach is to make internal Kubernetes DNS add-on respond to external DNS queries. The prime example of this is the CoreDNS k8s_external plugin. It works by configuring CoreDNS to respond to external queries matching a number of pre-configured domains. For example, the following configuration will allow it to resolve queries for svc2.ns.mydomain.com, as shown in the diagram above, as well as the svc2.ns.example.com domain:

k8s_external mydomain.com example.com

Both queries will return the same set of IP addresses extracted from the .status.loadBalancer field of the svc2 object.

These domains will still need to be delegated, which means you will need to expose CoreDNS externally with service type LoadBalancer and update NS records with the provisioned IP address.

Under the hood, k8s_external relies on the main kubernetes plugin and simply re-uses information already collected by it. This presents a problem when trying to add extra resources (e.g. Ingresses, Gateways) as these changes will increase the amount of information the main plugin needs to process and will inevitably affect its performance. This is why there’s a new plugin now that’s designed to absorb and extend the functionality of the k8s_external.

The new k8s_gateway CoreDNS plugin

This out-of-tree plugin is loosely based on the k8s_external and maintains a similar configuration syntax, however it does contain a few notable differences:

- It doesn’t rely on any other plugin and uses its own mechanism of Kubernetes object discovery.

- It’s designed to be used alongside (and not replace) an existing internal DNS plugin, be it kube-dns or CoreDNS.

- It doesn’t collect or expose any internal cluster IP addresses.

- It supports both LoadBalancer services and Ingresses with an eye on the service API’s HTTPRoute when it becomes available.

The way it’s designed to be used can be summarised as follows:

- The scope of the plugin is controlled by a set of RBAC rules and by default is limited to List/Watch operations on Ingress and Service resources.

- The plugin is built as a CoreDNS binary and run as a deployment.

- This deployment is exposed externally and the required domains are delegated to the address of the external load-balancer.

- Any DNS query that reaches the

k8s_gatewayplugin will go through the following stages:- First, it will be matched against one of the zones configured for this plugin in the Corefile.

- If there’s a hit, the next step is to match it against any of the existing Ingress resources. The lookup is performed against FQDNs configured in

spec.rules[*].hostfields of the Ingress. - At this stage, the result can be returned to the user with IPs collected from the

.status.loadBalancer.ingress. - If no matching Ingress was found, the search continues with the Services objects. Since services don’t really have domain names, the lookup is performed using the

serviceName.namespaceas the key. - If there’s a match, it is returned to the end-user in a similar way, alternatively the plugin responds with

NXDOMAIN.

The design of the k8s_gateway plugin attempts to address some of the issues of other solutions described above, but also brings a number of extra advantages:

- All external DNS entries and associated state are contained within the Kubernetes cluster while the hosted zone only contains a single NS record.

- You get the power and flexibility of the full suite of CoreDNS’s internal and external plugins, e.g. you can use ACL to control which source IPs are (not)allowed to make queries.

- Provisioning that doesn’t rely on annotations makes it easier to maintain Kubernetes manifests.

- Separate deployment means that internal DNS resolution is not affected in case external DNS becomes overloaded.

- Since API keys are not stored in the cluster, it makes it easier and safer for new tenants to bring their own domain.

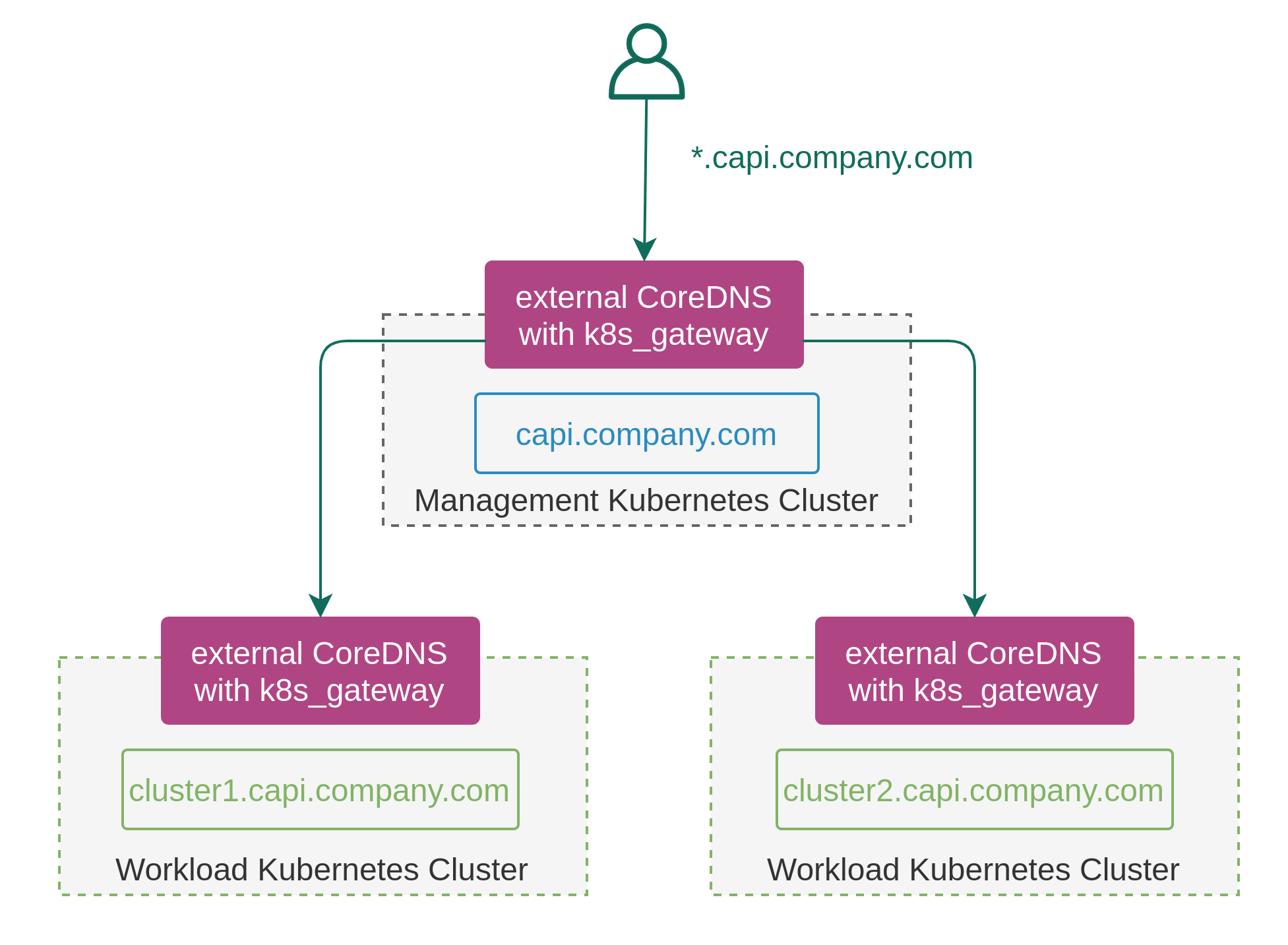

- Federated Kubernetes cluster deployments (e.g. using Cluster API) become easier as there’s only a single entrypoint via the management cluster and each workload cluster can get its own self-hosted subdomain.

The k8s_gateway is developed as an out-of-tree plugin under an open-source license. Community contributions in the form of issues, pull requests and documentation are always welcomed.